Left-Wing Extremism in Germany: A Resurgent Threat

Written by Elisa Garbil – 10.12.2025

For decades, discussions of extremism in Germany have been dominated by the spectres of right-wing and Islamist violence. The nation’s historical trauma and recent experiences with far-right terror have understandably captured most of the security community’s attention. Yet beneath this focus, another movement has persisted, one that is quieter, more fragmented, but increasingly professionalised: left-wing extremism.

Recent years have seen a slow but measurable resurgence in left-wing extremist activity across Germany and Europe. Once dismissed as marginal or nostalgic, the movement has demonstrated renewed energy, growing organisation, and a disturbing readiness for violence. The Bundesamt für Verfassungsschutz (BfV), which is Germany’s domestic intelligence agency, has sounded the alarm that left-wing extremism represents a serious and evolving threat to the free democratic basic order. Acts of violence, sabotage, and intimidation occur “almost daily”, the agency notes, often against the police or perceived right-wing opponents.

Ideology and Aims: The Absolutism of Equality

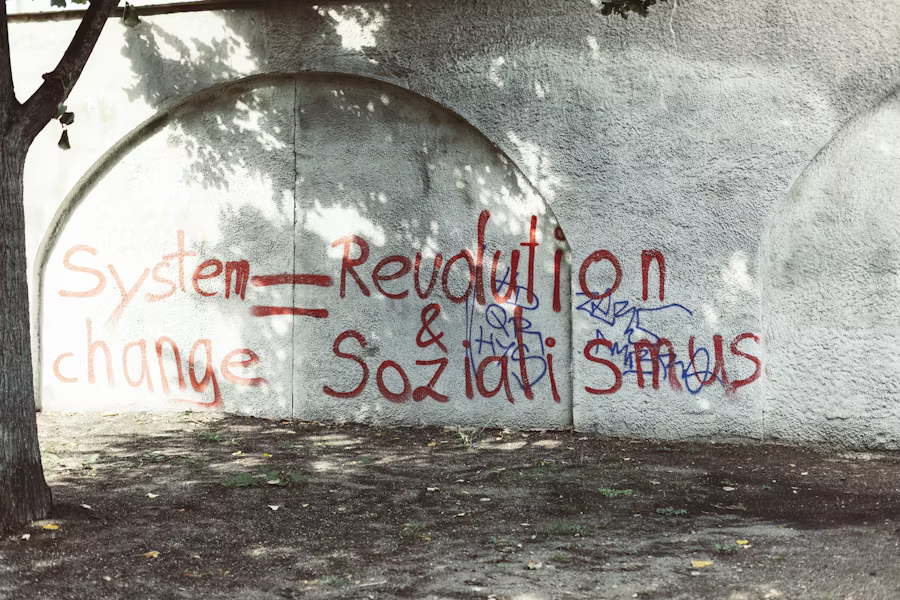

At its core, left-wing extremism in Germany is defined not simply by progressive ideals but by an absolutist approach to them. As the BfV defines it, left-wing extremism encompasses “all efforts directed against the free democratic basic order that are based on treating the values of freedom and (social) equality as absolutes”. This may manifest as an anarchist rejection of all authority or as a Marxist-Leninist drive to replace capitalism with a centrally controlled system.

For the ideological purist, capitalism and the state are inseparable enemies. Capitalism is seen as the “root of all evil”, perpetuating inequality and exploitation. Democracy is dismissed as a façade that masks capitalist oppression. As such, many extremists view reform as futile, as change can only come through revolutionary rupture.

This radical opposition to the state is not new. The legacy of groups such as the Red Army Faction (RAF) still looms over Germany’s collective memory. Yet today’s left-wing extremists differ from those Cold War predecessors. They are less hierarchical, less doctrinaire, and more networked. Many reject traditional party politics entirely, instead seeking autonomous, what they call, “free spaces” in which state authority is denied. Others cling to strict Marxist ideology, providing intellectual and moral justification for more militant wings.

The scene is therefore highly heterogeneous, encompassing autonomists, anarchists, and strictly ideological extremists. What unites them is the underlying conviction that the existing democratic and capitalist order is illegitimate, and its defenders, think of police, political parties, and private corporations, are fair targets.

The Structure of a Scene

The modern German left-wing extremist landscape is largely decentralised. The largest faction consists of autonomists, concentrated in major cities and university towns such as Berlin, Hamburg, and Leipzig. These groups reject external control, avoid formal leadership structures, and communicate through informal or encrypted channels.

The BfV estimates that more than one in four left-wing extremists is violence-oriented, meaning they are willing to use force against individuals or property to pursue political change. This share is significant as it represents a reservoir of actors capable of spontaneous or organised violent action.

Autonomist and anarchist circles thrive in urban ‘alternative’ spaces, think of squats, cultural collectives, and social centres that double as ideological hubs and logistical bases. Within these milieus, activists conduct discussions, plan demonstrations, and occasionally store weapons or incendiary materials. Their ideology emphasises self-defence against what they see as an oppressive state, but the definition of ‘defence’ has grown increasingly elastic.

The strictly ideological factions such as the Marxist-Leninist, Trotskyist, or anti-imperialist organisations, often distance themselves from direct violence, but they serve as ideological incubators. Their rhetoric legitimises militant action, providing the moral framework within which violence becomes not only permissible but necessary.

Together, these actors form an ecosystem where autonomous cells, digital networks, and informal alliances can mobilise rapidly when triggered by political or social events.

From Protest to Violence

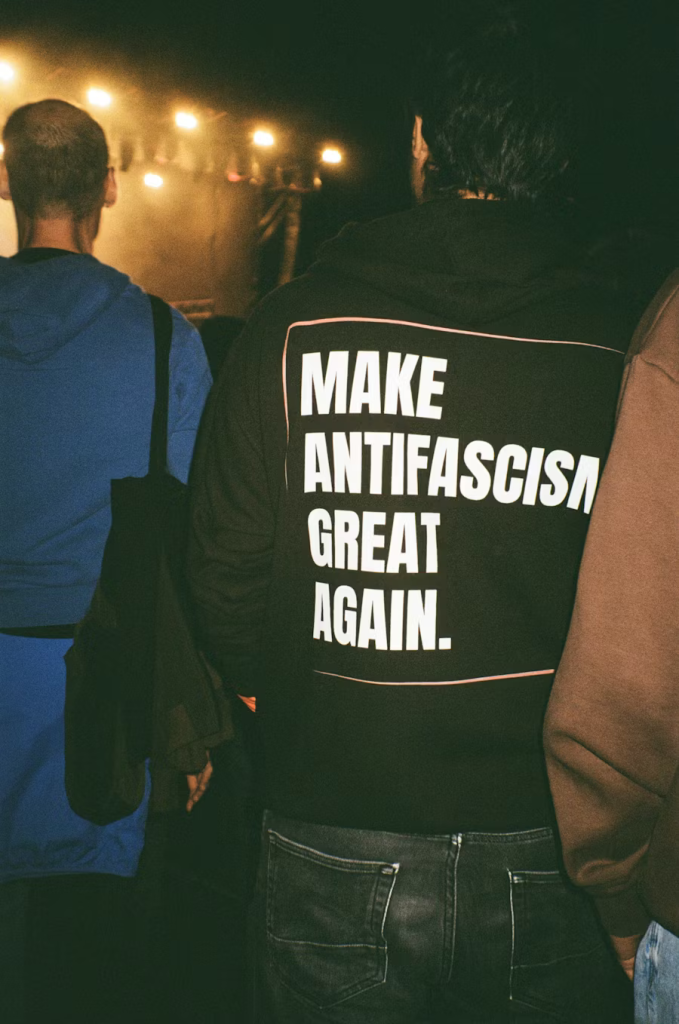

The transformation from activism to extremism often follows a familiar pattern. Many adherents enter the movement through legitimate political causes such as anti-fascism, climate activism, housing rights, or anti-capitalist demonstrations. These issues have become a bigger problem in all our societies, no matter our country. Extremist networks then embed themselves within these broader movements, blurring the line between protest and militancy.

Nonetheless, it is important to remember that not every anti-fascism, climate activism, housing rights, or anti-capitalist demonstrations are left-wing extremism.

By participating in democratic protests, extremists gain cover, legitimacy, and recruits. They exploit the moral energy of social movements while gradually introducing radical narratives that frame the state as inherently violent and oppressive, algorithms help with this a lot as well. Once this framing takes hold, violence against the state or its representatives becomes framed as defensive resistance rather than aggression.

The result is a continuum: from non-violent protest to militant confrontation, and occasionally to covert attack. This fluidity makes left-wing extremism particularly difficult to detect and counter.

Quantifying the Threat

Empirical data confirms that left-wing violence in Germany has not disappeared and that it has evolved. According to Statista’s compilation of German police crime statistics, acts of left-wing extremist violence rose sharply between 2019 and 2020, from 921 to 1,237 incidents. In more recent years, the trend has continued. By 2023, Germany recorded 727 violent offences attributed to left-wing extremists, compared with 602 the year before.

These figures show a steady rhythm of violence, rarely spectacular, but consistently present. The cumulative effect is one of attrition: a constant background of political aggression that erodes security and normalises confrontation.

At the European level, the 2017 Europol Terrorism Situation and Trend Report (TE-SAT) noted that left-wing and anarchist groups accounted for most completed attacks that year, namely 13 out of 16 terrorist incidents recorded in the EU. While most of these attacks caused property damage rather than fatalities, the data illustrates how the left-wing extremist current remains an active source of political violence on the continent. It is important to note that left-wing terrorism is more often property damage rather than attacking people.

The Engel–Guntermann Network: A Case Study in Escalation

If statistics provide the scale of the problem, the Engel–Guntermann network offers its anatomy. Between 2018 and 2020, this clandestine German cell carried out a series of targeted assaults against real or perceived right-wing extremists. The group’s operations were meticulously planned. Members conducted surveillance, trained for rapid ambushes lasting no more than 30 seconds, and used disguises and burner phones to evade detection.

According to a study published by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, the network was structured in concentric circles: a core leadership, a trained operational tier, and a wider support base. The participants were relatively young, many in their twenties, and some possessed combat experience from conflict zones such as Syria.

The group’s activity culminated in brutal beatings, chemical sprays, and organised raids. One victim survived a pre-planned ambush in Leipzig that could easily have turned fatal.

When German authorities dismantled parts of the network, similar attacks continued elsewhere, including in Budapest in 2023, suggesting either residual members or copycat structures. The authors of the West Point study concluded that the Engel–Guntermann case demonstrates a transitional form of extremism, poised on the boundary between violent activism and outright terrorism.

This evolution of small cells, into professionalism and cross-border cooperation, is what worries analysts most. It indicates a willingness not just to confront but to punish and terrorise opponents, which is new, as left-wing terrorism tends to be against property and infrastructure. Thus, echoing the early phases of terrorist escalation.

Assessing the Risk

A risk-based assessment considers not only intent but capability, opportunity, and consequence. In Germany’s case, left-wing extremists exhibit all four elements in varying degrees.

Motivation is clear and ideologically anchored: the belief that capitalism and democracy are inherently unjust systems requiring destruction.

Capability is growing, evidenced by training, transnational networking, and access to urban logistics. Opportunity arises from porous boundaries between protest and extremism, as well as from urban environments where state presence is contested.

The potential consequences range from moderate to severe. At one level, acts of arson, vandalism, and assault create a climate of fear in targeted communities and impose economic costs on public infrastructure. At another, more dangerous level, a transition to terrorist-style attacks, where targeting police, state institutions, or critical infrastructure is becoming normalised, could cause casualties and major disruption.

The BfV notes that attacks on energy, transport, and telecommunication networks have already caused millions in damage. These attacks strike at the state’s functional legitimacy, demonstrating vulnerability and undermining public confidence.

Escalation Pathways

Risk does not remain static, it evolves along certain pathways. For Germany’s left-wing extremist scene, several such trajectories are discernible.

- The shift from symbolic violence (burning cars, smashing windows) to targeted physical assaults. The Engel–Guntermann case exemplifies this trajectory. Deliberate, person-centred violence replacing property damage as the preferred method of political expression.

- Infrastructure sabotage. Anarchist and autonomist groups have attacked communication lines, train cables, and energy facilities. While casualties are rare, the intent to disrupt systems that symbolise capitalism and control is unmistakable.

- Transnational cooperation. German extremists’ involvement in attacks abroad, and the presence of foreign militants in German networks, suggest an emerging European ecosystem of left-wing militancy. Europol’s reporting indicates that such cooperation is no longer exceptional but increasingly normal.

- The digital pathway. Online radicalisation, encrypted coordination, and the use of alternative media to spread anti-state narratives. In these spaces, extremists construct echo chambers that justify violence as moral resistance.

Vulnerabilities and Exposure

From a risk management perspective, Germany faces several vulnerabilities that heighten exposure to this threat:

- Urban “free spaces”, such as Leipzig’s Connewitz district, act as logistical and ideological safe havens, where law enforcement encounters resistance and community sympathy limits effective intervention. These enclaves serve as laboratories for anti-state culture and as recruitment hubs for young activists.

- Universities and alternative subcultures provide another fertile ground. The combination of intellectual radicalism, social idealism, and peer validation can accelerate radicalisation. Research from Leiden University and the European Consortium for Political Research has shown that ideological socialisation in such settings can shift quickly from grievance to militancy, particularly when state repression is perceived.

- The blurring of activism and extremism further complicates prevention. When violent actors embed themselves in legitimate movements (environmental, housing, or anti-fascist protests) law enforcement faces a dilemma: intervene too strongly and risk political backlash, or hesitate and allow extremism to metastasise.

These vulnerabilities are compounded by under-prioritisation. Because left-wing extremists rarely cause mass casualties, their threat has historically received less attention and fewer resources than other forms of extremism. This underestimation creates a window for escalation.

Impact Scenarios

The risk spectrum ranges from disruption to disaster. A plausible near-term scenario is a coordinated sabotage campaign targeting energy or transport infrastructure. Such an operation could cause widespread disruption without requiring large resources, exploiting Germany’s dependence on interconnected networks. A more severe scenario involves a lethal assault on political opponents or law enforcement personnel. The Engel–Guntermann network’s preparation suggests this capability already exists. Were such an attack to result in fatalities, it could mark the psychological turning point where left-wing extremism in Germany crosses fully into terrorism.

The systemic risk, however, may be even greater than physical harm. Persistent extremist violence erodes public confidence in the state’s ability to maintain order. This delegitimisation, explicitly sought by left-wing radicals, can polarise society, feeding the very authoritarian reflexes they claim to oppose.

International Dimensions

Germany is not alone in facing this phenomenon. Europol has documented a resurgence of left-wing and anarchist terrorism across Europe, particularly in Italy, Greece, and Spain. Networks exchange tactics, training materials, and ideological texts across borders. German actors have participated in international protests and attacks, underscoring the transnational nature of the movement.

The Budapest incident, where German militants were arrested following violent anti-fascist actions, revealed operational cooperation with non-German extremists. Such mobility challenges national policing models, demanding enhanced intelligence sharing and cross-border coordination.

The ProtectUK LASIT threat assessment highlights similar patterns in Britain: small, fluid cells with ideological overlap between left-wing, anarchist, and single-issue causes (notably environmental activism). The European picture thus points to a pan-ideological convergence, where anti-capitalist, anti-fascist, and eco-radical narratives fuse into hybrid extremism.

The Risk Outlook

Looking ahead, most analysts foresee a moderate-to-high threat trajectory over the next three to five years. Several factors underpin this projection:

- Socio-economic environment: rising inequality, climate anxiety, and housing shortages, provides fertile ground for radical narratives that frame the state as complicit in injustice.

- The digital ecosystem allows ideological diffusion and coordination beyond geographical limits.

- Generational turnover within the movement ensures renewal: younger militants replace older ones, often with greater technological literacy and tactical sophistication.

Statistically, large-scale terrorist attacks remain unlikely, but targeted and disruptive violence is expected to persist or intensify. The combination of ideological motivation, tactical experience, and available targets makes a new cycle of violent activism probable. Unless countered, left-wing extremism could thus evolve into a chronic security risk capable of undermining democratic legitimacy from within.

Managing and Mitigating the Risk

For the security community, the response must be multifaceted. Intelligence agencies and police must adapt to the decentralised and networked nature of the threat, focusing on early detection of micro-cells and covert training activities. Monitoring open-source and encrypted communication channels can help identify patterns of mobilisation before they manifest in violence.

At the same time, authorities must engage with the sociopolitical environment that enables radicalisation. Overly repressive policing can confirm extremist narratives of state oppression, while excessive tolerance can allow extremism to entrench. Finding the balance requires nuanced community engagement, particularly in university towns and alternative subcultures.

Prevention efforts should include exit programmes for disillusioned activists, as the BfV already operates, and educational initiatives that reinforce democratic pluralism without demonising dissent.

Critical infrastructure operators, meanwhile, must integrate extremist threats into their risk management frameworks. Physical security, cyber resilience, and employee awareness are crucial, especially in sectors symbolically linked to capitalism or state control, such as energy, transport, and finance.

Finally, policymakers must treat left-wing extremism not as a lesser cousin of other threats but as a distinct and evolving category. It may be less lethal today, but its strategic objective, the delegitimisation of democracy, is no less destabilising.

The Quiet Return of a Familiar Adversary

Left-wing extremism in Germany is no relic of the 1970s. It is a living, adaptive, and increasingly international phenomenon. The movement’s ideological appeal to equality and justice cloaks a deeper hostility to democratic compromise. Its decentralised structure, professional tactics, and willingness to employ violence elevate it from nuisance to systemic risk. Germany’s experience illustrates a broader European challenge: how to defend democracy against those who claim to act in its name.

The risk is not only physical but moral, if extremists succeed in convincing sections of society that violence is a legitimate means of political expression, the democratic state may find itself eroding from within.

For now, left-wing extremism remains a contained but real threat. But the trajectory is worrying. Unless States recognise its evolving nature and adapt its counter-measures accordingly, they may yet face the return of a familiar adversary, one that fights not to seize power, but to make power itself impossible.