Afghanistan After the Exit: Security Myths, Gender Apartheid, and the Costs of Walking Away

When Afghanistan made international headlines again in August 2021, the country was often pictured as an ending: the end of a twenty-year intervention, the end of Western responsibility, the end of a failed state-building experiment. Is it really? As Dominic Bowen argues in The International Risk Podcast, Afghanistan is not a closed chapter, and still represents an ongoing risk for the international community to manage. In his conversation with Emily Winterbotham, RUSI expert on counterterrorism, humanitarian governance with a specialty in gender conflict, and regional power politics, he discusses the consequences of disengagement.

The episode challenges diverse dominant narratives we hear in the media about security improvements, about Taliban governance, and the idea that the US has fully stepped out and that the world can move on. Afghanistan today, they argue, is not quieter because it is stable, but because it is repressed and structurally isolated from the international system.

A country shaped by intervention and abandonment

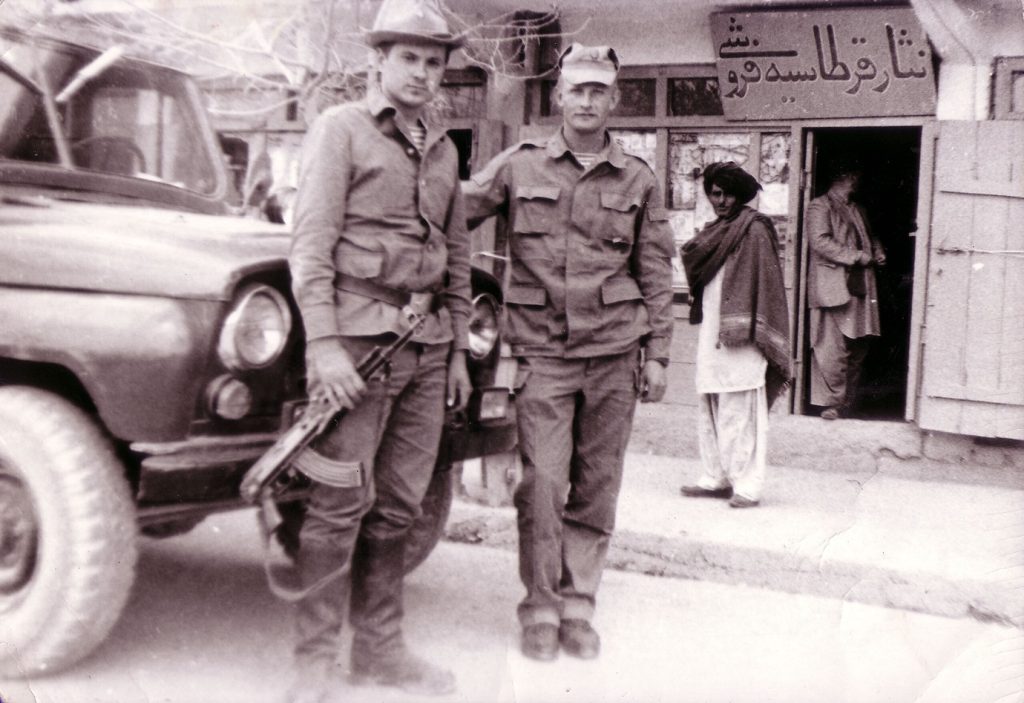

Soviet troops in Gardez, Afghanistan, in 1987. By Кувакин Е. (1987); scanned and processed by User:Vizu (2009); размещено согласно Permissions – own scan photo E.Kuvakin by personal collection, CC BY-SA 3.0

Afghanistan’s modern political history has been written through the continued intervention of external powers. Recognised as a sovereign state by the United States in 1934, the country fluctuated throughout the Cold War between Western and Soviet influence. Contrary to contemporary Taliban narratives, Afghan society in the 1950s and 1960s experienced significant social reform, particularly for women, who gained access to education and employment during that period.

The 1973 coup that led to the abolition of the monarchy and a communist takeover in 1978 marked the beginning of an extended period of instability. Indeed, Soviet military intervention in 1979 internationalised the conflict, transforming Afghanistan into a proxy warfare battleground during the Cold War. The rise of the Mujahideen, supported by the United States, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and other countries, succeeded on the military power front, but left behind a deeply traumatized Afghan society, barely holding on through fragmented power structures and armed factions.

As Winterbotham has highlighted in her research, the international community repeatedly failed to prioritise inclusive political settlements. After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and the collapse of the Najibullah government in 1992, warlordism flourished. The Taliban’s emergence in the mid-1990s was not a mere accident but a reaction to widespread insecurity caused by corrupt and violent governance.

The Taliban’s return: surprise or inevitability?

Taliban fighters patrol in Kabul, Afghanistan, Aug. 19, 2021. VOANews, Taliban Fighters Now Manning Checkpoints in Afghan Cities December 08, 2021 2:00 AM; by Associated Press

In this episode, Winterbotham explains that the Taliban’s rapid takeover in August 2021 did not come as a shock to those closely monitoring the situation. Years before the collapse, research programmes were already reporting deteriorating conditions: the state was no longer legitimate, and security issues led to local-level negotiations between Taliban commanders and government actors.

What surprised many policymakers, she suggests, was not so much the Taliban’s strength as the speed at which the Afghan state collapsed. This failure reflected long-standing instabilities such as contradictory allegiances, corruption, and a conflict that was never a simple binary between “government” and “rebels.”

Emily echoes this perspective, noting that prolonged engagement in conflict zones often reveals how little outsiders truly understand. Afghanistan, like many conflicts, cannot be reduced to counterterrorism matters; we need to analyse the deeper political and social drivers of instability.

Rethinking terrorism and security narratives

Regional context around Afghanistan illustrates how nearby states, including Pakistan and Iran, interact with the Taliban-ruled state and related security concerns. Source: Afghanistan regional geography and neighbour relations (Britannica)

One of the most persistent claims since 2021 is that Afghanistan has become more secure under Taliban rule. Winterbotham offers a more cautious assessment. While levels of visible violence have declined, this does not equate to long-term stability.

She argues that Afghanistan was never an ideal base for transnational terrorism. Both its isolated geography and limited infrastructure make it less than ideal for global terrorist operations than is commonly assumed. The threat was often exaggerated, both in 2001 to justify intervention, and in later years to sustain it.

That said, extremist groups remain present. Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) has adapted -rather than disappeared- to the scrutiny, shifting from mass recruitment to infiltration and online radicalisation. Al-Qaeda maintains ties with Taliban factions, particularly the Haqqani network. The Taliban have contained some threats more effectively than expected, but the absence of independent intelligence access makes a reliable assessment difficult, says Emily.

Therefore, Winterbotham stresses that containment is not the eradication of the threat. Risks are suppressed, not resolved, and could resurface if internal Taliban cohesion weakens -as Dr. Arian Sharifi explains.

Gender apartheid as a security issue

Afghan women march during a women’s rights protest in Kabul on January 16, 2022. Source: Women and girls in Afghanistan are fighting for their rights, 1 November 2022, INTERNATIONAL AND CRISIS ASIA (Amnesty International © Wakil KOHSAR / AFP)

Perhaps the most devastating transformation since 2021 has been the systematic removal of women and girls from public life. UN experts have described the situation as “gender apartheid”.

Winterbotham rejects the idea that women’s rights were uniformly protected before the Taliban’s return, noting that many Afghan women already lived under conservative restrictions. However, what distinguishes the current period is the scale and intent of exclusion. Women have been banned from secondary and higher education, removed from most forms of employment, barred from public spaces, and denied access to basic services.

Winterbotham describes this as a deliberate political project: the policies appear punitive to her, an attempt to erase the social gains of the past two decades and reassert ideological, extremist dominance.

The humanitarian consequences are severe. According to the UN, more than 23 million Afghans require assistance, and nearly 15 million face acute food insecurity. Restrictions on female healthcare workers have exacerbated maternal mortality and limited access to care. Experts reported in 2023 that depression and suicide were widespread among adolescent girls prevented from pursuing education.

Most importantly, our expert links gender exclusion directly to long-term insecurity, drawing on peacebuilding research and arguing that sustainable stability is unlikely without inclusive governance. Excluding half the population undermines legitimacy and very much isolates Afghanistan further from international engagement.

Why Russia recognises the Taliban

In this photo released by Russian Foreign Ministry Press Service on Oct. 4, 2024, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov, right, and Acting Foreign Minister of Afghanistan’s Taliban movement Amir Khan Muttaqi pose for a photo prior to their talks in Moscow, Russia. (Russian Foreign Ministry Press Service via AP, File)

Russia’s decision to formally recognise the Taliban government did not come as a shock to Winterbotham. She frames it not as ideological alignment but as strategic risk management: Moscow has long-standing diplomatic and intelligence networks in Afghanistan and prioritises transnational threats prevention, particularly from ISKP. And from Russia’s perspective, the Taliban represent a nationalist actor with limited external ambitions -thus being a lesser threat than Islamic State affiliates.

Therefore, recognising the Taliban-run state as such allows Moscow to reinforce its influence in and on the region, all while distancing itself further from the West.

Central Asian states, India, and China have all adopted these kinds of approaches, border stability over human rights -particularly women’s rights-perceived as secondary interests if not non-issues.

Western disengagement and moral trade-offs

“Chaman” border crossing partially reopens after Pakistan-Afghanistan ceasefire. Picture: Nizami Brothers, project constructors.

Despite fears of renewed Europe-targeted terrorism, Winterbotham argues that the direct security threat to Europe has not dramatically increased. Migration flows from Afghanistan remain significant but are shaped by poverty constraints rather than forced mass new departures. For neighbouring states like Pakistan and Iran, concerns about refugees and extremist spillovers exist but are not new.

The United States and its partners have provided billions in humanitarian assistance since 2021, largely channelled through NGOs rather than Afghan institutions. However, Taliban authorities have extracted significant revenue through taxes and fees, raising concerns about undisclosed financing.

Winterbotham understands the current approach of Western governments of not recognising and avoiding Taliban institutions, but warns of unintended consequences of non-intervention, which is legitimising repression through silence -including the closure of health facilities and the marginalisation of women. She is particularly critical of counterterrorism financing laws that make it difficult to support small, local organisations -the very actors most capable of resisting exclusion at the community level.

Above all, she argues that Afghanistan’s sense of betrayal runs deep. As she notes, “international hypocrisy” was deplored by Afghans long before 2021, particularly in the early decision to empower abusive warlords in the name of short-term stability.

Lessons for the future

Afghan girls read the Quran in the Noor Mosque outside Kabul this month, Ebrahim Noroozi / AP. Source: Afghan girls face uncertain future after a year of no school, The Associated Press, NBCNews.

Reflecting on past failures, Winterbotham rejects the “better the devil you know” logic that shaped post-2001 international intervention policy. Research conducted across Afghan provinces revealed general resentment toward warlords backed by the international community, resentment that fuelled Taliban support and undermined state legitimacy.

The lesson: exclusion is costly. Durable peace requires an acceptance of complexity, and negotiating with controversial actors may be uncomfortable, but ignoring social realities is worse.

Thus, Afghanistan today stands as a warning: walking away from a conflict does not make its risks disappear; it scatters them across borders, generations, and makes our global systems less prepared to manage them.

One Comment