After Maduro: Power, Illicit Economies, and the Unravelling of Venezuela’s Political Order

The capture of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro by the United States forces on the 3rd of January 2026 marks one of the most dramatic geopolitical events in the Western Hemisphere in decades. However, as stressed by both our host, Dominic Bowen, and our guest, Dr. Brian Fonseca in this episode of the International Risk Podcast, this moment in history cannot yet be taken as a rupture and democratic reset. Instead, Maduro’s arrest embodies Venezuela’s institutional decay, oil-dependent authoritarianism, its militarised governance, and the internationalisation of the country’s internal crisis.

To understand what happens next, and why Venezuela’s future remains deeply uncertain, it is necessary to see this arrestation as part of the country’s long political history and to examine the power structures that may very well thrive post-Maduro.

Venezuela’s resources and political fragility

Shutterstock image, uploaded 27/01/2026

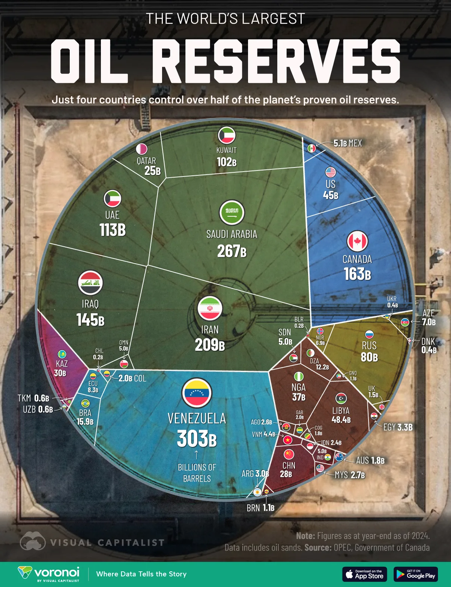

Spread out over 912,000 square kilometres and home to roughly 28.5 million people, Venezuela, situated between Colombia, Brazil, and Guyana, holds the world’s largest oil reserves to date –over 300 billion barrels– as well as vast amounts of gold, iron, and other strategic minerals. These riches, however, have long been a curse as much as a blessing.

Indeed, since independence in the early nineteenth century (1810-1823), Venezuela’s political development has been marked by cycles of authoritarianism and populism, and has long been combating institutional fragility. As a classic “rentier state,” the country’s governments relied mostly on external actors’ rents rather than domestic taxation, which has led to a weakening of financial accountability of elites misappropriating funds and neglecting the population.

Oil wealth financed modernisation under dictators like Juan Vicente Gómez in the early 20th century, but the political inclusion introduced by Chávez did not make up for the lack of economic transformation. The 1958 transition to civilian rule under the Puntofijo Pact brought stability through elite power-sharing, but at the cost of exclusion and systemic corruption. When austerity measures sparked the violent Caracazo uprising in 1989, the social contract collapsed. Three years later, the failed military uprisings of 1992, led by Hugo Chávez, paved the way for a radical reordering of Venezuelan politics -and thus, society.

The Bolivarian Revolution and the illusion of participation

Chávez’s election in 1998 inaugurated the Bolivarian Revolution, a project framed as the “refounding” of the Republic. The 1999 Constitution restructured the state into five branches -executive, legislative, judicial, electoral, and citizen- and proclaimed a “participatory and protagonistic democracy.” Communal councils and social missions expanded access to services, while oil revenues were supposed to be redistributed.

Politically, Chávez had electoral legitimacy with truly symbolic anti-imperialism and nationalist rhetoric, rooted in the figure of Simón Bolívar. As Brian Fonseca explains in the episode, Bolívar’s mythology was embedded not only in the political discourse -following the Libertador’s cry for the liberation of American colonies until today- but even in the renaming of the armed forces as the “Bolivarian Armed Forces,” giving the military a symbolic mission tied to regime survival.

LaCroix, Décès de Hugo Chavez, l’homme fort de Caracas, Gilles Biassette, March 6, 2013

CRWFlags.com, The Bolivarensian Coat of Arms, “Piedra del Medio” (The Middle-River Stone) located in front of capital Ciudad Bolivar. Credit: Guillermo T. Aveledo, 3 January 2001

Despite early reductions in poverty and inequality, Venezuela remained dependent on imports, price controls, and hydrocarbon rents. High oil prices masked these weaknesses, and when oil prices fell, the system proved very fragile.

Maduro’s rule: collapse without Chavisma

Nicolás Maduro inherited Chávez’s project in 2013, but not his charisma. Elected by a contested margin (51.95%), Maduro kicked off his presidency with a deteriorating economy -Venezuela experienced one of its worst economic collapses with a GDP contracted by roughly 75% between 2014 and 2021, and oil production fell from nearly 3 million barrels per day to under a million -and experts predict a drop to 400 000 bpd by February.

The social consequences were catastrophic. According to UN agencies, nearly 8 million Venezuelans fled the country, creating the largest displacement crisis in modern Latin American history. Those who remained endured shortages, repression, and declining public services and purchasing power.

The Economist, As Venezuelans go hungry, their government holds a farcical election, May 17th 2018, Caracas,

After the opposition won the National Assembly in 2015, Maduro decided to further solidy his power rather than reform: judicial interventions stripped the legislature of its powers in 2017; elections continued, but without meaningful guarantees; and by the mid-2020s, Venezuela had become an electorally authoritarian, “militarised hybrid regime”.

Who holds Power now?

In the episode, Dominic challenged the widespread assumption that Maduro’s capture automatically dismantled the regime. Fonseca agreed, emphasising that power in Venezuela had long been distributed across overlapping centres rather than concentrated in a single individual.

On January 28, 2026, three pillars remain decision-makers in Venezuela: the military under Defence Minister Vladimir Padrino López, an institution that Fonseca repeatedly described as the “ultimate arbiter of continuity or change”; the internal security and intelligence apparatus, associated with Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello; and Delcy Rodríguez, who embodied the political legacy of Maduro himself and initially assumed de facto leadership.

En.Ara.Cat, The faces of Venezuela’s ‘New government’: it all stays in the family. Albert Naya, January 10, 2026. Credit: Agêncies/ARA

These actors were not united by ideology but by years of “coup-proofing” their mandates, through corruption of the military and illicit economies, while fostering competition among branches. As Fonseca noted, the United States had long hoped for fractures within the armed forces, but none occurred.

Fragmentation, violence and illicit economies

The greatest immediate risk following Maduro’s capture was fragmentation. Fonseca outlined two dangers: fighting amongst regime elites and reactions of violent non-state actors on Venezuelan soil.

Over the past decade, illicit economies have become central to Venezuelan governance. As oil revenues collapsed under sanctions and mismanagement, gold mining, narcotics trafficking, fuel smuggling, and arms flows could fill the gaps. Criminal groups, local militias, and remnants of Colombian insurgencies such as the ELN and the FARC operated under an unspoken tolerance from the state, but Maduro’s removal disrupted this equilibrium.

The Guardian, May 11th, 2011, Venezuela attacks report suggesting ties between Chavez and FARC rebels. “The report claims that Venezuelan officials gave FARC rebels a haven, using them to train pro-government militias”. Photograph: Scott Dalton/AP

Some actors might consolidate; others might migrate to countries with a weaker rule of law, such as Ecuador or Peru; still others could confront state forces directly.

The United States’ plan

What, then, was Washington’s endgame? In the podcast, Fonseca framed the U.S. policy as a combination of long-term aspirations with short-term leverage. Restoring democracy remained an objective, particularly for Secretary of State Marco Rubio, whose personal history and regional focus shaped his priorities. But immediate concerns like oil, migration, and transnational crime were more concrete.

Visual Capitalist, All of the World’s Oil Reserves by Country, in One Visualization, December 30, 2025. Bruno Venditti. Credit: Sam Parker

Rather than “governing” Venezuela, the Trump administration sought to “run” it economically -in other words, by controlling access to oil revenues to shape political behaviour. Therefore, Venezuela’s reserves, the largest in the world, made energy central to this strategy.

International Law and a changing world order

Maduro’s capture raised profound legal and normative questions. If a foreign power can seize a sitting head of state, what prevents similar actions elsewhere? Fonseca’s response suggested that the answer lies in a shifting global context.

Great powers, he argued, increasingly prioritise interests over norms, coercion over restraint, and unilateral action over multilateral governance. International law and institutions are no longer viewed as neutral frameworks but as constraints to be navigated when they clash with strategic goals. This trend, visible not only in U.S. policy but also in Russian and Chinese behaviour, signals a gradual erosion of the post-1945 rules-based order, Fonseca warns.

Spiegel International, The End of the West, Dirk Kurbjuweit, November 11th, 2024. Image description: The return of Donald Trump to the White House marks the end of an era. Credit: Brian Snyder / REUTERS.

External Allies: Cuba, Russia, and China

Fonseca’s earlier research, echoed in the podcast, suggests bringing some nuance to the claim that Maduro was supported by foreign powers. Cuban intelligence played a critical role in regime security and monitoring elite loyalty, but its footprint was often exaggerated in political discourse. Russia’s involvement, while symbolically significant, remained transactional only -arms sales, oil ventures, and the opportunity to disrupt the U.S., rather than a commitment to a relationship with Venezuela.

China, by contrast, represents the most complex challenge. Beijing extended tens of billions of dollars in loans backed by oil deliveries since 2000. This economic entanglement will not disappear with Maduro. Any U.S. attempt to reshape Venezuela’s economy must deal with Chinese claims and debt restructuring.

A flawless operation, an uncertain aftermath

The military operation to remove Maduro and his family from Venezuela -described by Fonseca as one of the most sophisticated he has witnessed in a long time- demonstrated overwhelming U.S. superiority across air, land, sea, cyber, space, and electronic warfare domains. But whether elements of the Venezuelan military tacitly stood down remains an open question.

What is clear is that Maduro’s survival had always rested on military loyalty. Unless that institution fractures or is restructured, Venezuela’s political trajectory will remain the same.

Conclusion: beyond the illusion of rupture

Maduro’s capture did not end Venezuela’s crisis: it exposed how deeply-rooted it is. Centuries of inequality, decades of oil dependence, and years of elite institutional corruption. As Fonseca warned in the episode’s closing moments, the broader risk extends beyond Venezuela: a world drifting away from shared rules toward nearly Hobbessian power politics.

For Venezuela, the path forward will be neither quick nor straight. For the international community, the capture of Venezuela’s most recent leader raises uncomfortable questions about sovereignty, intervention, and the future of global order. The fall of one man has not resolved the revolution he inherited, but it has forced the world to look at the consequences of letting a state break up for so long.