The Dam of All Dams: Assessing China’s Hydropower Ambitions on the Yarlung Tsangpo in Tibet

It’s kind of China’s moonshot. Nothing like it has been built before. And when a moon mission happens, the world is watching.”

Brian Eyler on the International Risk Podcast

On 19 July 2025, Chinese Premier Li Qiang presided over the ceremony marking the start of construction of the world’s largest hydropower dam project on the Yarlung Tsangpo River in Tibet, following its approval in December 2024. Hailed domestically as “the project of the century” and the “dam of all dams”, it has also been described as “the dam of death”.

The 60,000 megawatt (MW) project—referred to as the Medog or Motuo Hydropower Station, though its official name remains unconfirmed—will comprise five cascading hydropower dams spanning roughly 250 kilometres of the Yarlung Tsangpo River. It is expected to be completed after 2030, with commercial operations planned for 2033. Once operational, it will be the most productive hydroelectric facility in the world, generating an anticipated 300 billion kilowatt-hours annually, three times the capacity of the Three Gorges Dam and roughly equal to the UK’s entire power production.

Despite its grandeur, many details remain uncertain. Much about the project’s design, financing and resettlement plans remains undisclosed. What is clear, however, is that behind Beijing’s economic and clean energy justifications lie significant environmental, social and geopolitical risks.

The Yarlung Tsangpo: Geography and Context

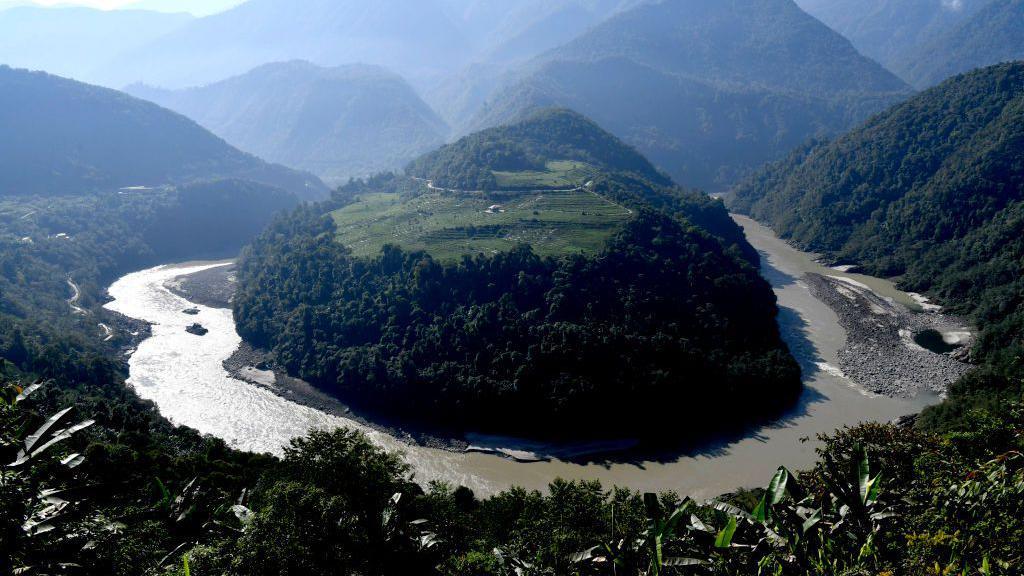

The Yarlung Tsangpo flows across the Tibetan plateau, beginning in western Tibet’s glaciers before entering India’s Arunachal Pradesh where it becomes the Siang River. Further downstream in India, it is known as the Brahmaputra before entering Bangladesh and emptying into the Bay of Bengal. Situated within what is often called the “Third Pole”—the largest store of freshwater outside the North and South Poles and the headwaters of several of South Asia’s major rivers—the Yarlung Tsangpo is Tibet’s longest river, the world’s highest major river and one deeply embedded in Tibet’s history and culture.

The Medog installation is designed to harness the river’s immense power at its Great Bend where it makes a sharp U-turn around the Namcha Barwa mountain, dropping 2,000 metres in elevation within just 50km through the Earth’s deepest and longest canyon. These geographical and geological features makes it ideal for energy generation but also one of the most seismically volatile and environmentally sensitive locations on Earth.

Assessing China’s Reasons for Building the Dam

Economic Argument

The Medog hydropower project carries a projected pricetag of 1.2 trillion yuan ($167 billion), over four times that of the Three Gorges Dam, making it one of the most expensive infrastructure projects in history. Beijing presents the dam as a cornerstone of national development and a major economic stimulus. For the Chinese state, the project exemplifies the ability to combine economic modernisation with energy transition goals; a feat of engineering that would demonstrate China’s technological leadership to the world.

Markets reacted enthusiastically to the inauguration. Government bond yields rose, infrastructure and construction stocks surged, and companies linked to cement, explosives and tunneling hit daily trading limits. Citigroup estimates that over its decade-long construction period, the project could boost China’s GDP by 120 billion yuan ($16.7 billion) annually.

Despite the positive market reaction, both Brian Eyler and Palmo Tenzin on The International Risk Podcast caution that this enthusiasm obscures deep economic and social risks. Tenzin argues that the hydropower dam’s benefits are concentrated among energy producers, local government officials and industrial coastal centers, while Tibetans bear the immediate costs of displacement, loss of land and environmental and cultural degradation. “The costs are quite high,” she notes, “they’re immediate and they largely fall on Tibetans”.

Eyler underscores that projects like this reflect a fundamental imbalance in China’s development model, where the periphery regions fuel growth in the industrial east: “The way that the Chinese can expand and exploit its periphery provides this type of imbalance to occur, where benefits can be thrown far away from the site of exploitation, and the losses are local and not replaced by benefits”. Eyler calls for a more comprehensive evaluation of social and cultural losses, such as the value of losing a monastery or the loss of nomadic life, which is usually overlooked by the state.

The costs are quite high, they’re immediate and they largely fall on Tibetans.”

Palmo tenzin on the international risk podcast

Tenzin also notes, “No one has really talked about the economic viability of these projects… no one has thought this project through”. Building five cascading dams in one of the world’s most seismically active and remote regions with harsh weather conditions demands vast supporting infrastructure—roads, tunnels and transmission lines—which will only amplify costs and risks. “It’s an extremely risky project,” Eyler concludes, “and there’s no real guarantee it will work”.

Clean Energy Argument

Beijing frames the Medog project as a “win-win”—a clean energy solution that furthers both development and environmental goals. Promoted as part of China’s 14th Five-Year Plan and 2060 carbon neutrality pledge, the dam is touted as a “coal killer” that will cut fossil fuel dependence and help address its air pollution crisis. Domestically, the project bolsters the Chinese Communist Party’s narrative that hydropower is key to achieving self-sufficiency and sustaining China’s manufacturing dominance through cheap electricity. With hydropower accounting for nearly 20% of China’s total electricity generation and China leading the world in hydropower capacity, the Medog system is also presented not only as a symbol of technological power but of global climate leadership.

However, Eyler and Tenzin challenge the narrative of hydropower as “clean”, highlighting how it obscures the dam’s profound human and environmental costs, especially when viewed through the lens of distributional justice. Tenzin also acknowledges that local Tibetans are not opposed to hydropower itself but to its inequitable and unaccountable implementation. “Local residents also want reliable, clean energy,” she says, “but the question is what are the costs and benefits, and how are they distributed?”. Most of the energy will be transmitted eastward as part of Xi Jinping’s West-to-East Electricity Transfer Project. In doing so, Beijing reinforces a long-standing pattern of extraction and control, where Tibet’s natural resources fuel national develompent goals but its people see few of the benefits, raising concerns about Tibet’s role as an energy colony.

Large-scale hydropower produces substantial emissions from reservoir methane, construction and deforestation, all of which undermine its “clean” image. Tenzin highlighted that “the scientific literature is overwhelmingly actually quite against hydropower because of the impact it has on river systems, both local and downstream”.

Beijing has released no comprehensive environmental impact assessment despite claiming the project will prioritise ecological protection. Such claims ring hollow given China’s record on the Yangtze and Mekong, where ecosystems have been disrupted, exacerbated droughts and caused irreversible biodiversity loss. The Yangtze was once home to immense biological diversity, home to around 400 fish species, 6,000 plant species and 500 terrestrial vertebrates, but the construction of the dam altered the river’s natural flow, causing habitat fragmentation and extinction of native species.

The way that the Chinese can expand and exploit its periphery provides this type of imbalance to occur where benefits can be thrown far away from the site of exploited, and the losses are local and not replaced by benefits.”

Brian Eyler on the International Risk Podcast

Hydropower as Statecraft and Social Control

Beijing portrays the Medog project as part of a broader campaign to modernise Tibet through development. Nevertheless, critics argue that the project is an attempt to reshape regional identity and reflects repeated patterns of coerced relocation and assimilation seen under earlier ‘modernisation’ drives. Thousands of Tibetans face displacement, dismantling of communities, loss of livelihoods and access to sacred sites. Tenzin explains that those resettled “often lose connection to their land and community”, becoming alienated and vulnerable in unfamiliar urban settings. This relocation policy, she argues, “serves this other goal of assimilation…placing people into urban centers where they can be monitored easily”.

Far from a “win-win”, Tibetan advocates frame the Medog project as resource extraction imposed on a marginalised frontier region with the potential to eradicate the region’s unique identity and the spiritual ties that rivers like the Yarlung Tsangpo.

The project also reflects a deeper historical narrative. In Chinese political culture, river control has long equated to political authority and stability. The great Yangtze flood of 1443 threatened the stability of the Ming dynasty, while an estimated 2 million people died when the Yangtze flood in 1931. This has fed into the Chinese belief that rivers need human control to abate natural disasters and promote state legitimacy. Today, with climate change and increasing water scarcity looming, projects like the Medog represent China’s latest quest to harness the power of its river, framing it as essential for securing China’s future.

Geopolitical Leverage and Downstream Fears

Another reason China might be building this dam is to use it as a strategic tool, allowing Beijing to manipulate flows in times of tension. As the upper riparian power, China insists that the Yarlung Tsangpo’s management falls within its sovereign rights. In July, Beijing stated that the river’s development “is a matter within the scope of China’s sovereign affairs”. For India and Bangladesh, this heightens concerns over potential water manipulation.

Eyler calls these fears “justified”, citing China’s operations on the Mekong, where dams have driven “wet season droughts” and “daily irregular fluctuations” from sudden releases. Such patterns could devastate agriculture and fisheries downstream along the Brahmaputra, which sustains nearly 100 million people.

Arunachal Pradesh’s Chief Minister Pema Khandu has warned of “water bombs”—sudden, unwarned releases of water—that could obliterate farmland and livelihoods, posing an existential threat, especially as the Medog dam system is located just 30km from the Arunachal Pradesh province. Meanwhile, Bangladesh fears further stress on its fragile water systems.

The absence of any basin-wide water-sharing agreement deepened these anxieties, especially as there are no frameworks in place for information exchange. This issue is compounded by the ongoing territorial dispute over Arunachal Pradesh which Beijing claims as “Zangan”, part of South Tibet, further politicising the basin and evalating the stakes of any hydrological dispute. Water disputes worldwide often become particularly volatile when they intersect with broader geopolitical tensions, and the conditions surrounding the Medog are ripe for water to be politicised and securitised.

While India criticises China’s unilateralism, itself has preferred to pursue bilateral rather basin-wide agreements to preserve its upstream advantage. Its recent suspension of the Indus Water Treaty undermines its credibility and exposes a degree of hypocrisy, as the actions it has taken on the Indus against Pakistan risks normalising the very water weaponisation it warns China against.

Many details about the Medog hydropower project remain undisclosed, and key concerns remain unanswered. For Beijing, it is a symbol of modernisation and national strengthen; for Tibetans and downstream neighbours, it is a project fraught with danger. Both Eyler and Tenzin call for a pause in construction and a reassessment of hydropower’s trust costs.

As Eyler points out, “it’s kind of China’s moonshot. Nothing like it has been built before. And when a moon mission happens, the world is watching.”

One Comment

Comments are closed.