Iran Under Pressure: Sanctions, Stagnation, and the Limits of Economic Coercion

Iran has faced more than a decade of sustained economic pressure. Inflation has remained above 40 percent. The rial has experienced repeated episodes of sharp depreciation. Oil exports, once the central pillar of state revenue, have been significantly constrained by sanctions. From the outside, it looks like a system in permanent crisis. Yet despite these pressures, Iran’s economy has not collapsed, nor has its political system fractured in the way many external observers predicted.

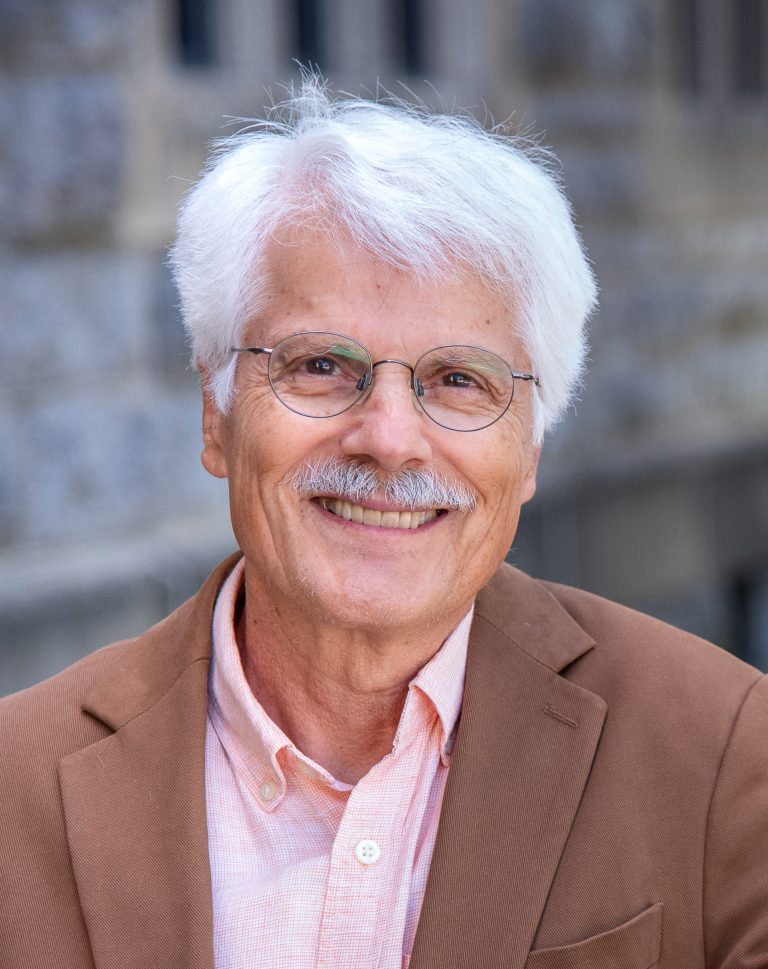

In a recent episode of the International Risk Podcast, Professor Djavad Salehi-Isfahani joined Dominic Bowen to examine how sustained sanctions have reshaped Iran’s economic structure, social expectations, and political resilience. What emerges from the discussion is not a story of implosion, but of endurance. The Iranian economy today is not breaking. It is stagnating.

A Decade of Structural Stagnation

Salehi-Isfahani is clear about when the decisive shift occurred. “It has been a prolonged period of stagnation. And it started around 2011.” That was the moment when targeted sanctions evolved into comprehensive measures that effectively excluded Iran from large parts of the global financial and trade system.

During the 2000s, Iran’s economy had grown at more than five percent annually, buoyed by high oil prices and export revenues. Sanctions disrupted that trajectory fundamentally. “What sanctions did is they reduced Iran’s oil exports sometimes by half, sometimes by two-thirds.” The immediate result was contraction. The longer-term consequence was the disappearance of growth momentum.

This distinction matters. A temporary recession can be reversed. Structural stagnation reshapes expectations for an entire generation.

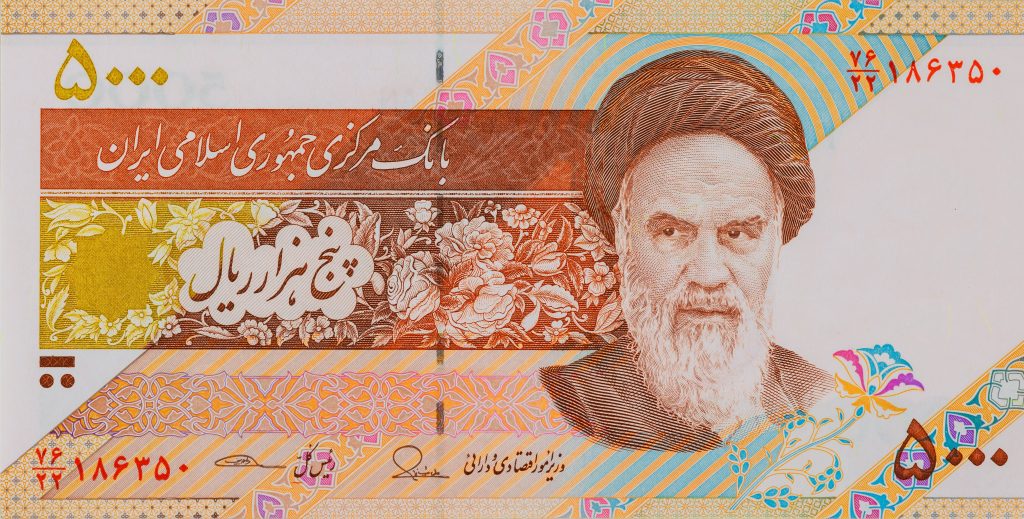

Currency Collapse and Inflation Transmission

Two episodes of dramatic depreciation frame Iran’s recent economic history: the 2012 collapse following expanded sanctions and the 2018 collapse after the United States withdrew from the nuclear agreement.

“When the currency depreciates as it did in 2012 by 200 to 300 percent… again in 2018… the currency collapsed by 200 percent,” Salehi-Isfahani explains.

In an economy that imports significant quantities of food, consumer goods, and intermediate inputs, exchange rate shocks transmit directly into domestic prices. “Iran imports a lot of food… a lot of goods… and a lot of intermediate goods. So the price shock comes from the exchange rate immediately to businesses.”

Inflation becomes embedded. Depreciation fuels price increases. Rising prices erode savings and weaken confidence. Yet the crisis does not present as empty shelves. “If you go to Iran, you see very few items that are lacking… the shelves are stocked well.” The constraint is not availability. It is affordability. Goods exist. Purchasing power does not.

Poverty, Redistribution, and the Limits of Shock Management

Before the intensification of sanctions, poverty had fallen to roughly 10 percent of the population. Iran’s post-revolutionary policies included extensive subsidies and rural investment, contributing to improvements in health, education, and income distribution. When sanctions reduced national income, poverty began to rise again.

The state attempted to cushion the impact through a nationwide electronic cash transfer system. Funds are deposited directly into household accounts. The infrastructure works. But redistribution cannot compensate for shrinking national income. “When you have a big shock, like you lose half of your oil exports or more, there is no way to prevent real incomes from falling.”

Bread remains subsidised and accessible. However, red meat has “basically” disappeared from the food basket of the poor. Hunger may not be widespread, but dietary quality has declined. Many Iranians feel they “don’t participate in the decisions that result in sanctions… but then the people have to pay for it.” The national income shrinks, and the burden is distributed across society.

The Middle Class and the Erosion of Savings

If the poor experience contraction through diet and daily consumption, the middle class experiences it through anxiety. “The middle class is always in danger of sliding down,” Salehi-Isfahani observes.

Inflation at 40 to 45 percent undermines predictability and long-term planning. Savings held in bank accounts lose real value rapidly, even where nominal interest rates are positive. “You can imagine you have savings in the bank. If you wait six months, a third of it is gone. If you wait a year, half of it is gone.”

This erosion does not generate dramatic headlines. It generates stress. Households attempt to preserve outward markers of stability while absorbing financial losses quietly. Social expectations remain intact even as purchasing power declines. Over time, this creates economic pressure that feels deeply personal.

Youth, Opportunity, and the Forward-Looking Crisis

Perhaps the most consequential dimension of prolonged stagnation concerns young people, as Salehi-Isfahani notes in an interview with Harvard’s Belfer Center. In the episode, Salehi-Isfahani reflects on his own adolescence in Iran, recalling a time when effort seemed reliably rewarded. “I knew that if I studied hard, I could get into university. I knew if I got into university, I would get a job.”

Today, that expectation chain has weakened. “Only the top one to five percent get into good schools that can then guarantee a job.”

The frustration is not limited to current living standards. It concerns the probability of future mobility. It concerns whether effort translates into opportunity. When asked to summarise the core of societal frustration, Salehi-Isfahani focuses directly on this demographic. “I would focus on the youth. They all have parents. Their pain translates into parents’ pain.”

Inflation is visible. Lost expectation is less visible, but potentially more destabilising over time.

Sanctions and Political Resilience

Given sustained economic hardship, why has Iran’s political system remained intact? Salehi-Isfahani offers a simple but important observation. “Economies don’t collapse. People get up in the morning… they go to the farm, go to the store.”

Economic activity continues even under strain. Markets function. Goods remain available, even if prices are high. The economy has shrunk and stagnated, but it has not disintegrated.

Salehi-Isfahani notes political systems, however, are more fragile. In Iran’s case, elite cohesion has held. A cohesive national identity, a distinct ideological foundation rooted in Shia political thought, historical memory of foreign intervention, and scepticism toward external actors promising regime change all contribute to resilience. Sanctions have increased hardship, but they have also reinforced narratives of external hostility. For many Iranians, the prospect of regime collapse raises fears of instability and chaos rather than immediate transformation.

Reform Through Contraction or Expansion

The policy question that emerges is whether economic contraction induces reform or entrenches resistance. One approach assumes that sufficient pressure will fracture regimes from within. Another suggests that strengthening middle-class opportunity creates conditions for internal reform.

Salehi-Isfahani aligns with the latter view. Durable change, he suggests, is more likely to emerge through domestic social evolution than through economic strangulation. Sanctions have demonstrated an ability to increase hardship without guaranteeing political transformation. Internal social pressure, by contrast, has at times produced incremental shifts.

Continuity Under Pressure

Taken together, the Iranian case points to continuity under strain rather than imminent collapse. Sanctions have reduced growth, increased poverty pressures, eroded savings, and reshaped expectations. They have not dismantled economic activity or fractured elite cohesion.

The Iranian economy continues to function, albeit at a lower trajectory and under persistent stress. The broader implication is not that sanctions are ineffective. They clearly impose costs. Rather, the lesson is that economic coercion does not mechanically translate into political change. Structural resilience, ideology, identity, and historical memory shape outcomes as much as fiscal constraint.

Iran today represents a system compressed, constrained, and anxious, but not broken.