Episode 263: NATO in a Shifting World and the Next Chapter of Collective Defence with Dr. Jamie Shea

In this episode Dominic Bowen and Dr. Jamie Shea unpack NATO at a moment of historic change. Find out more about how fear has re-emerged as a unifying force within the Alliance, the political and economic challenges of reaching unprecedented defence spending levels, industrial bottlenecks and Ukraine’s role as a partner in innovation and supply, the rising threat of hybrid warfare from cyberattacks to sabotage and disinformation, the volatility of United States diplomacy and the implications of a “big three” world dominated by Washington, Moscow, and Beijing, the long-term challenge of sustaining support for Ukraine, NATO’s expanding ties with the Asia-Pacific, and the future of medium powers seeking autonomy in an era of great power competition, and more.

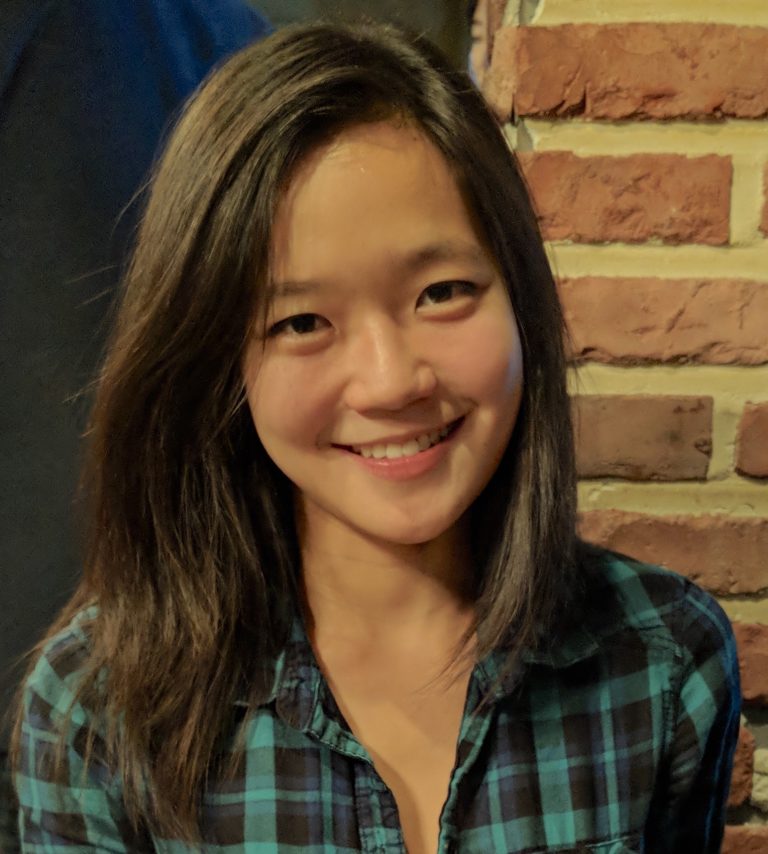

Dr. Jamie Shea CMG is Professor at the College of Europe Natolin, Senior Fellow for security and defence at Friends of Europe, and Senior Advisor at the European Policy Centre in Brussels. He is also Senior Counsel to the Founder and CEO of Fanack/The Chronicle and Fanack Water. Previously, Dr. Shea was Professor of Strategy and Security at the University of Exeter, and for 38 years he served as a member of NATO’s International Staff, holding senior positions including Deputy Assistant Secretary General for Emerging Security Challenges, Director of Policy Planning, and NATO Spokesman. He has also taught at institutions including the College of Europe in Bruges, the University of Sussex, and the American University in Washington DC, and is a Senior Transatlantic Fellow of the German Marshall Fund and Associate Fellow at Chatham House.

The International Risk Podcast brings you conversations with global experts, frontline practitioners, and senior decision-makers who are shaping how we understand and respond to international risk. From geopolitical volatility and organised crime, to cybersecurity threats and hybrid warfare, each episode explores the forces transforming our world and what smart leaders must do to navigate them. Whether you’re a board member, policymaker, or risk professional, The International Risk Podcast delivers actionable insights, sharp analysis, and real-world stories that matter.

The International Risk Podcast – Reducing risk by increasing knowledge.

Follow us on LinkedIn and Subscribe for all our updates!

Transcript:

Dominic [00:00:00]

Hi, I’m Dominic Bowen, host of The International Risk Podcast, where we unpack the risks shaping our world. Today we’re exploring NATO at a moment of strategic inflection. Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine and its continued hybrid attacks across Europe have reshaped the continent’s security posture.

NATO has expanded coordination, reconsidered threats, and member states have committed to some of the most ambitious defence spending plans in recent history. But with these shifts come complex questions. How can NATO maintain unity amid diverse national interests and shifting domestic politics? Can the Alliance continue to deliver resilience, innovation, and foresight while retaining public trust in an age of contested truths?

To help us navigate these questions, I’m joined by Professor Jamie Shea. Jamie served in NATO for nearly four decades, including as Deputy Assistant Secretary General for Emerging Security Challenges, Director of Policy and Planning, and NATO Spokesman during pivotal moments in the Alliance’s history. He has received NATO’s Meritorious Service Medal and is a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George. Today, he is Professor at the College of Europe in Natolin, Senior Fellow at Friends of Europe, and Senior Advisor at the European Policy Centre in Brussels.

Jamie, welcome back to The International Risk Podcast.

Jamie [00:02:00]

Thanks very much, Dominic. It’s great to be back. Though I suppose it could mean one of two things: either I was so good the first time that you couldn’t resist inviting me again, or I was so bad you thought I deserved a chance to make amends. We’ll see which it is by the end of this conversation.

Dominic [00:02:30]

I think it was definitely the former. We had excellent feedback last time, and I’m really looking forward to today. NATO’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was remarkable for its cohesion. Since then, Finland and Sweden have joined the Alliance, member states have made historic defence spending commitments, and NATO has intensified strategic dialogue with partners in the Indo-Pacific. But alongside that cohesion, there are also new pressures.

How is NATO managing to navigate such divergent national politics, especially as allies face domestic constraints and leadership cycles?

Jamie [00:03:00]

Well, fear, Dominic, is often a stronger unifier than love. And fear is definitely back in NATO capitals. After Russia’s first incursion into Ukraine in 2014, with the annexation of Crimea and the war in the Donbas, there was already unease. But after the full-scale invasion in 2022, that unease turned into something much sharper.

Now, Ukraine isn’t a NATO member, so there’s no obligation to defend it. But it is a neighbour, and the concern has always been that if Putin succeeded in subjugating Ukraine and the West did nothing, he might then be tempted to move against a NATO country. That is why Finland and Sweden abandoned decades of neutrality almost overnight. They recognised that being a partner or a friend of NATO is not the same as being protected by NATO.

As Benjamin Franklin once said, we either hang together or we hang separately. And collective defence has always been the real reason countries join the Alliance.

Dominic [00:05:00]

You’re absolutely right. Fear often highlights exactly what is worth acting on. Stephen Pressfield once wrote, “Are you paralysed with fear? That’s a good sign. The more scared we are, the more certain we should be that we need to act.” And that seems to be what NATO is doing.

You mentioned defence spending, which is obviously a huge issue. Back in 2016, President Trump was threatening to pull the United States out of NATO if members weren’t spending 2 percent of GDP on defence. Now we are talking about 5 percent. If Europe actually reaches that level, what does it mean? Is it a dangerous escalation, or could it be a positive shift?

Jamie [00:06:00]

It means two things. First, more capable armed forces: well-equipped, well-trained, and ready to fight and defeat Russia if it ever came to that. NATO is, of course, in the business of deterrence. By demonstrating readiness, through investment and through exercises, the message to Moscow is clear: not today, not tomorrow. You will not succeed.

Second, it is about convincing the public. Shifting that much money into defence will not be easy when citizens also want funding for schools, welfare, or healthcare. Leaders will have to show that defence investment brings wider economic benefits. Think of shipbuilding in Glasgow, where the UK has tied defence budgets to job creation. Or Italy talking about a new bridge to Sicily, justified partly by its military utility. Defence can be framed as dual-use, creating economic opportunities alongside security.

But there is a challenge. In the 1950s, defence spending created millions of jobs. Today, robotics, automation, and AI mean factories can produce tanks or aircraft with far fewer workers. So the benefits are real, but perhaps not on the same scale.

Dominic [00:09:00]

That’s fascinating. But even with big budgets, we’ve already seen bottlenecks. Ammunition shortages, production lines running years behind demand. Germany’s hundred-billion-euro special fund will take a decade to turn into actual capabilities. Sweden dismantled most of its defence industry in the 1990s. Is Europe really going to be able to rebuild capacity, or will it simply end up buying American weapons?

Jamie [00:10:00]

Good question. The reality is that both Europe and the United States face the same bottlenecks. You cannot rely entirely on Washington. Their industries also scaled down after the Cold War, and they too need to rebuild. For years, governments told industry “get ready, orders are coming.” Industry replied, “show me the contracts first.” That gap slowed everything.

Now we are seeing momentum. Companies like Rheinmetall in Germany or Leonardo in Italy have seen share prices surge on new contracts. But rebuilding takes time: recruiting skilled workers, training them, and re-establishing supply chains. Ukraine, interestingly, has developed real capacity under wartime pressure. They can produce long-range drones and artillery at scale. Increasingly, NATO countries are partnering with Ukraine not as a charity case but as an industrial partner.

And another point: governments want private capital involved. Pension funds and banks have often avoided defence for ESG reasons, treating it like tobacco. That attitude is changing. Defence is being reframed as a socially responsible investment because it underpins democracy itself.

Dominic [00:17:00]

That leads us to another point. Over the summer we saw a surge in Russian hybrid attacks across Europe. Sabotage, cyber, disinformation campaigns. While we’ve been talking about tanks and budgets, it’s these asymmetric threats that are already testing resilience. You were NATO’s Deputy Assistant Secretary General for Emerging Security Challenges. How should Europe be thinking about these threats today?

Jamie [00:18:00]

The home front is now as important as the battlefield. We’ve seen undersea cables and pipelines sabotaged. Finnish prosecutors recently charged Russian sailors after an incident that damaged telecommunications between Finland and Estonia. In the UK, there were arrests linked to a Russian plot to blow up warehouses storing equipment for Ukraine. We see drones flying over air bases. We see cyberattacks every day, despite twenty years of investment. And we see disinformation targeting elections from Moldova to Hungary.

The good news is that governments are responding more quickly. Legal frameworks are improving. NATO has deployed a permanent naval task force in the Baltic Sea. Social media companies are under new obligations through the EU’s Digital Services Act. We are not powerless. But it is a constant contest, and vigilance cannot lapse for even a moment.

Dominic [00:21:00]

Recently we saw President Trump meet Putin on US soil, then Zelensky immediately afterwards, before rushing European leaders into Washington. What lessons should NATO take from this kind of volatile diplomacy?

Jamie [00:22:00]

That nothing can be taken for granted. The pace of diplomacy has accelerated. One day you think a position is fixed, the next day it is in play again. European leaders are flying to Washington at a moment’s notice to shore up positions. This is the world we live in.

It also signals a shift: the United States, Russia, and China increasingly act as a “big three,” settling global affairs on their own terms. Europe risks being sidelined. Medium powers will have to adapt to a world where they cannot simply rely on a superpower protector.

Dominic [00:25:00]

And if peace in Ukraine is not imminent, NATO needs to think about sustainable support. What does long-term support look like, especially if the US becomes more isolationist?

Jamie [00:26:00]

We may be heading towards something resembling Cold War containment. Ukraine needs to remain viable: enough territory, resources, and access to the Black Sea to function. It will require Western security guarantees, and possibly NATO or US troops stationed on its soil.

Even if Russia keeps some territory, the priority is preventing further aggression. In the Cold War, the Soviet Union did not advance an inch beyond what it had in 1945, because NATO drew a protective line. We may need to do the same for Ukraine, building prosperity behind that line until Russia itself changes.

Dominic [00:29:00]

NATO is also building ties with Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. Is the Alliance spreading itself too thin, or is this globalisation of NATO necessary?

Jamie [00:30:00]

It is necessary. Medium powers feel squeezed, so they are banding together. We face common threats: disinformation, supply chain vulnerabilities, authoritarian assertiveness. Cooperation benefits everyone.

I don’t see NATO extending Article 5 to Asia, but pragmatic collaboration is here to stay. And our Asia-Pacific partners have already supported Ukraine with sanctions, weapons, or diplomacy. It has to be a two-way street, but for now the incentives to work together are strong.

Dominic [00:32:00]

As we wrap up, Jamie, what are you watching most closely right now?

Jamie [00:33:00]

First, Ukraine. There seems to be momentum towards negotiations, but any peace has to be on Western terms, not Putin’s. Second, Iran, where recent strikes could create conditions for renewed nuclear talks, though that remains uncertain. Third, Gaza, where Israel risks winning wars but losing peace. And finally, Sudan, which is currently the world’s worst humanitarian crisis yet receives too little attention.

Dominic [00:35:00]

Thank you for raising Sudan and for joining us again. It has been another fascinating conversation.

Jamie

Always a pleasure, Dominic. Thank you for the invitation.

Dominic [00:36:00]

That was Dr. Jamie Shea, former senior NATO official and one of the Alliance’s most seasoned insiders. His insights offer valuable guidance as NATO prepares for a new global order.

Today’s episode was produced and coordinated by Katerina Mazzucchelli. I’m Dominic Bowen, host of The International Risk Podcast. Thanks for listening. We’ll speak again next week.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.