Security, Climate Change, and Risk in the Arctic and the High North

The Arctic and the High North are undergoing rapid transformation. Climate change is reshaping the physical environment, while shifting alliance dynamics and renewed geopolitical competition are altering how states think about security, access, and risk in the region. Yet despite growing attention, the Arctic is often framed through simplified narratives that overstate militarisation, exaggerate commercial opportunity, or collapse distinct regional dynamics into a single strategic storyline.

In a recent episode of The International Risk Podcast, Dr Paal Hilde joined Dominic Bowen to examine what is actually changing in the Arctic and the High North, where risks are real, and where they are frequently misunderstood. The discussion highlights the need for a more precise understanding of climate-driven change, regional variation, and strategic restraint.

Climate change as the primary driver

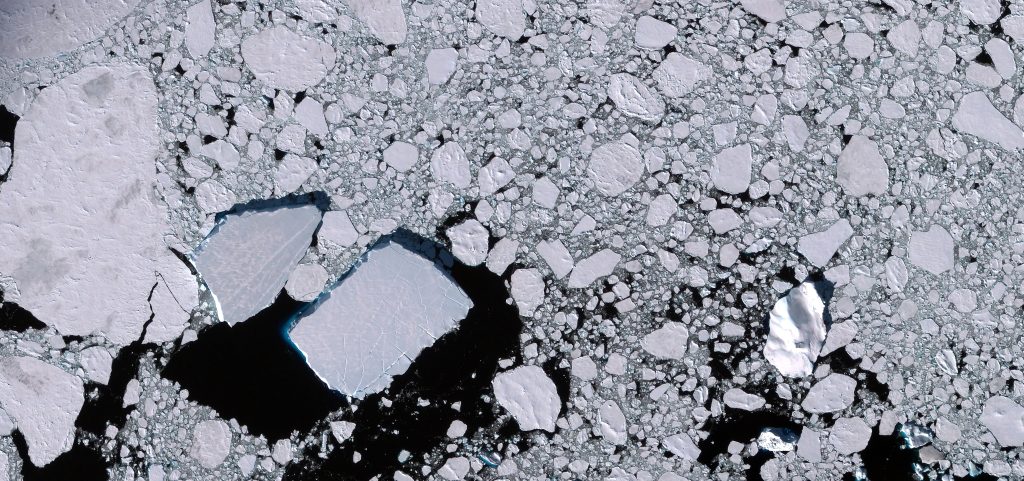

In the episode, Dr Hilde describes climate change as “one of the key drivers, or perhaps even the key driver” of change in the Arctic, highlighting how melting sea ice is opening a “new world ocean” that brings both opportunities and challenges. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) 2025 Arctic Vision and Strategy picks up the same theme, describing a “fundamental transformation” driven by rapid warming, shrinking sea ice, coastal erosion, and permafrost thaw that is now central to U.S. thinking about the region.

Crucially, both the podcast and recent analysis stress that less ice does not mean an easy operating environment. Dr Hilde underlines that even with reduced ice cover the Arctic still has winter darkness, rough weather and dangerous floating ice, so it remains very different from a “normal” global ocean. A 2025 study of Arctic shipping governance shows that these conditions, combined with uncertainty and sparse infrastructure, keep risk and cost far higher than on established routes, even as summers become more ice‑free

On land, Hilde points to thawing permafrost as a growing problem, with once‑solid ground softening and undermining roads, buildings and pipelines. Work on health and environmental security in Arctic Yearbook 2025 paints a similar picture, warning that permafrost degradation and coastal erosion are already damaging critical infrastructure and creating new environmental and public‑health risks in several Arctic communities.

Regional variation matters

A key message from the conversation is that there is no single Arctic. Dr Hilde explains that while it is sometimes useful to talk about the Arctic as one region, the differences between sub‑regions are “very, very big”, and that “the High North” in NATO terms really means the European Arctic. Sebastian Knecht makes a similar argument in the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, describing Arctic governance as increasingly “fractured” and warning that treating the Arctic as a single strategic space hides crucial regional differences.

Dr Hilde notes that the European Arctic stands out because it is relatively warm and habitable, thanks to warm water flowing north through the North Atlantic, which supports more people, more settlements and more visible activity than in northern Canada or Siberia. By contrast, much of the North American Arctic consists of small, remote communities with limited transport links, a reality spelled out in Washington’s Implementation Plan 2025–2026 Arctic Research, which highlights severe infrastructure gaps and climate‑driven hazards in Alaska.

Shipping, resources, and commercial expectations

The episode pushes back against the idea of an imminent Arctic shipping revolution. Dr Hilde recalls the early‑2000s expectations of a major oil and gas boom and a surge in international transit shipping, but shows how shale oil and gas, sanctions and commercial risk have deflated those hopes, with flagship projects like the Shtokman gas field eventually shelved. NOAA’s 2025 strategy similarly notes that while Arctic resources exist, high costs, harsh conditions and global energy transitions make many large new fossil projects hard to justify over the long term.

On shipping, Dr Hilde underlines that most current traffic along the Northern Sea Route is either Russian domestic shipping or trade between Russia and China, while on the North American side it is mainly internal services between Canadian and Alaskan ports. Detailed work on Arctic shipping shows that growth has been modest and uneven, with high insurance premiums, the need for specialised Polar Code‑compliant ships and short sailing seasons limiting broader commercial uptake

He also highlights the growing environmental risk from an ageing “shadow fleet” of tankers moving Russian oil to China through Arctic waters in summer, often with poor equipment and oversight. A 2025 Euronews/ICCT analysis shows that black‑carbon emissions from ships linked to EU trade in the Arctic have nearly doubled over the past decade and are contributing to faster local sea‑ice loss, underlining how poorly regulated traffic can deepen the very climate risks that make the region more accessible.

Security dynamics and alliance posture

On security, Dr Hilde traces how Russia rebuilt its military presence in the north from around 2007-08, feeding claims of “militarisation of the Arctic”. Since 2014, and especially after 2020, NATO navies and air forces have responded with more activity of their own, including Royal Navy and US Navy patrols in the Barents Sea and flights by U.S. strategic bombers over the region, intended to signal presence and deterrence. A 2025 report from the Foreign Policy Research Institute argues that the alliance’s northern posture after Finland and Sweden’s accession is about better situational awareness, coordination and resilience across the North Atlantic and Arctic, rather than an unchecked build‑up.

At the same time, Dr Hilde stresses that Russia has strong reasons to keep tensions low in the Arctic, from protecting its strategic submarines on the Kola Peninsula to maintaining prospects for future economic activity. Research supports this reading, suggesting that despite sharper great‑power competition, major actors still have clear incentives to avoid escalation in the Arctic and to preserve at least minimal cooperation through institutions like the Arctic Council.

Environmental and societal risk

The conversation also foregrounds environmental and societal risks that often slip behind big‑picture strategic narratives. Dr Hilde notes that Indigenous and local communities, around five million people across the broader Arctic, depend on ecosystems and species that are adapted to sea‑ice conditions, and that disappearing ice and shifting habitats are already disrupting hunting, travel and local food systems. Arctic Yearbook 2025 adds that permafrost thaw, unstable ground and changing ice conditions can damage water and fuel infrastructure, mobilise pollutants and make emergency response far more difficult in small settlements

New resilience projects are trying to put communities at the centre of the response. A 2025 initiative led by George Mason University and funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation is developing “digital twin” models and new foundation technologies so Arctic towns can anticipate permafrost and coastal hazards and adapt infrastructure before it fails. The 2025-2026 U.S. Arctic research plan likewise calls for more co‑designed work with Indigenous and local partners, reflecting Dr Hilde’s emphasis that the people who live in the Arctic are not just spectators to great‑power competition but central to any realistic discussion of risk and security.

Managing risk without escalation

Taken together, the podcast and recent research show an Arctic that is changing quickly, but not in the simple ways suggested by talk of a new “Great Game”. Dr Hilde’s analysis and NOAA’s 2025 vision both underline that climate change is the primary driver opening the region up, while also making storms, erosion, infrastructure failure and environmental accidents more likely.

For governments, businesses and communities, this means the real task is to focus on specific, rising risks, such as fragile infrastructure, poorly regulated shipping, shadow fleets and permafrost‑damaged settlements, rather than lean on dramatic but misleading narratives of inevitable militarisation. In that sense, the High North looks less like a ready‑made frontline and more like a stress test of how well societies can manage complex, climate‑driven risks under pressure, with success depending as much on governance and restraint as on raw capability.

One Comment