Afghanistan: what future for the country under Taliban rule?

In this episode of The International Risk Podcast, Dominic Bowen is joined by Dr. Arian Sharifi, Chief Strategy Officer at PercedgeResearch, to examine the evolution of the political situation in Afghanistan since the fall of Kabul in August 2021. The conversation assesses both regional and international risks linked to terrorism, economic, humanitarian, and political risks associated with the Taliban rule.

Afghanistan today: what led to the current politics?

Afghanistan’s modern political history has been marked by successive internal conflicts and fragile state-building efforts. Officially recognized by the United States in 1934, Afghanistan initially moved towards modernization and reforms, including expanded rights for women during the 1950s and 1960s, but quickly fell into decades of trouble.

The 1978 communist coup and the Soviet invasion of 1979 sparked the rise of the Mujahideen, a guerrilla resistance supported by the U.S., Pakistan, and Saudi-Arabia. When the Soviets withdrew in 1989, the country was left fractured. Civil war and the emergence of the Taliban in the mid-1990s transformed Afghanistan, with promises of order quickly replaced by repressive theocracy and international isolation. Insurgency, corruption, and fragile institutions prevented lasting stability in the early 2000s. On August 15, 2021, Kabul fell after the US agreed with the Taliban to a withdrawal in 2019, plunging Afghanistan back into Taliban rule, with dire humanitarian and geopolitical consequences.

The recognition of the Afghan State by Russia: any impact on world order?

In April 2025, Russia abandoned the “terrorist” designation for the Taliban and recognized the State as such. According to Dr. Sharifi, this decision has not impacted the political scene, as the full recognition of the State by the international community is fundamental for diplomatic liberties, and the entrance of Afghanistan into the ‘Bretton Woods system -an important institution to be part of for facilitated trade worldwide. The country would need to be represented at the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and at the United Nations – a situation that no one predicts.

Political stability achieved through human rights violations and isolation

Our guest recognizes the Taliban as instigators of stability in the country, showcasing a decrease in terrorist attacks, close to none, and a notable infrastructure policy to rebuild the country. A 2023 report on Terrorism of the U.S Department of State showcases a reduction in terrorist attacks in Afghanistan, including a 72% decrease in the use of Improvised Explosive Devices by 72%.

Most importantly, Arian points out the complete territory dominion by the Taliban, which hadn’t happened for 50 years in Afghanistan. This was achieved by chance, as, on the one hand, no other power resisted the Taliban at the time, and on the other hand, because the Republic went under. As our expert explains, the group broke all odds, still holding the fort over four years later.

However, this stability comes at great cost: the over-restriction of liberties and public life. Music and education for women are publicly prohibited, and men are obligated to grow beards when working for the government. Moreover, although a special commission is dedicated to convincing Afghan residents overseas to come back to their home country, their actions are heavily restricted, ensuring they don’t try to oppose the state.

Overall, indicators of governance, women’s rights, education, jobs, and freedoms are very low.

Assessing terrorist groups and their immediate, middle-term, and long-term threats

Arian makes a distinction between “west-oriented”-focused terrorist organisations (Al-Qaeda, the “Indian Sub-continent” – sub-group of Al Qaeda -, ISIL-K) and those who are “regionally-oriented”, focusing on Central Asian countries other than Afghanistan (the East Turkistan Islamic Movement of the Shujan province in China, peopled by minority Uigurs; the IMU – Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan -; Jaimati Ansarullah of Tajikistan; and the dismantled Sunni Iranian group Jundullah). Moreover, Pakistani terrorist groups like the TTP (Tahlik Taliban Pakistan) are the most active in Pakistan, attacking “every other day or two”, according to our guest, and are believed to have some bases in Afghanistan.

Dr. Sharifi assesses the TTP and ISIL-K’s activities as being minor threats to Afghanistan, the Taliban having repressed their activities; the ISIL-K is believed to be operating underground only in Afghanistan today.

About the U.S., Sharifi refers to “Counterterrorism over the horizon”, as American security experts call it, or the monitoring of these groups by the U.S. from afar, through drones mostly. According to him, the U.S. also considers that the mentioned groups do not represent a major immediate threat to the West anymore, save ISIL-K – although he doesn’t rule out the possibility of a resumption of terrorist attacks in the future.

The international economic interests and risks of the Baluchistan-Pakhtunkhwa regions: impacts of the Afghan-Pakistan conflicts

Two regions represent an issue to the Pakistani government: the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, formerly the North-eastern frontier with Afghanistan, and Baluchistan. Historically, the population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is Pashtun, hence Afghanistan’s resolve to claim this region as Afghan. Moreover, the TTP’s activity in the region and the Pashtun movements’ for the right to self-governance contribute to more turmoil as years go by.

Similarly, the Balochis, historically Afghans, refute the Pakistani power over the territory, and attacks often occur in the region. The BLA and TTP are believed to have a haven in Afghanistan, which further fuels the conflict.

Moreover, Afghanistan and Baluchistan are very rich in mineral resources. International sanctions limit trade, but China has been able to sign “over 300 mining contracts with the Taliban government”, as mentioned by Arian – Pakistan and Turkey entertain mining contracts there as well. Turkey-Afghanistan exports represent $300 billion a year, and Western countries are starting to turn towards the Central Asian region for mining. However, Sharifi reminds us of the fears of Western countries regarding security in the region, based on Pakistan’s demonstrated incapacity to secure its country since the 1970s and the development of General Zia’s “Islamisation program”. Moreover, the development of nuclear programs, which led to radicalisation, the emergence of terrorist groups, and insurgency from soldiers, adds to the perceived business risks.

High poverty and angry farmers since the ban on opium production

The Afghan statistical economy is officially stabilised, but poverty is really high. According to the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, “over 62.3% of the Afghan population, amounting to more than 25 million individuals, are poor.”.

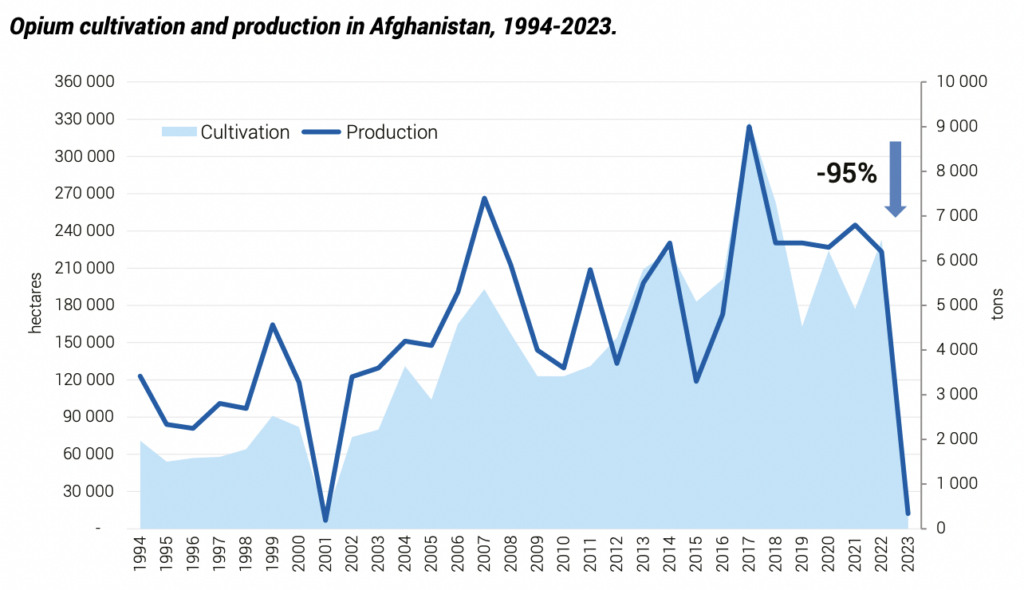

Why is that? As explained by Arian Sharifi, opium production did drop to 95%, but heroin production has “sustained more or less the same level”.

Moreover, previous years’ excess of production compared to demand left major reservoirs of opium and heroin, now sold at more than six times the original price, leading to higher revenues.

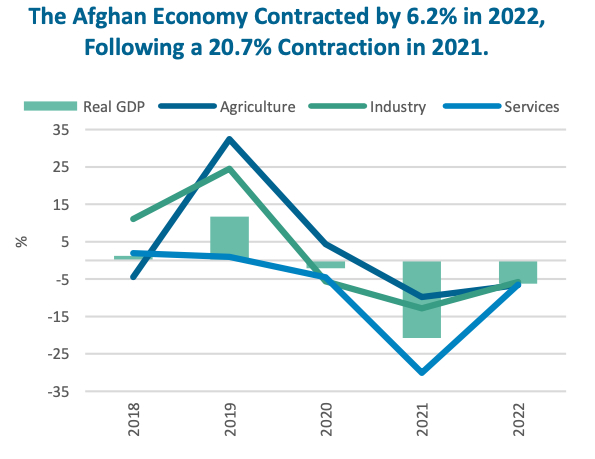

The following graph shows a relative economic stability in the last few years, after a 30-point drop in Real GDP between 2019 and 2020.

However, Sharifi warns that should production be kept at the same low rates, the economy will drop. There needs to be an “alternative livelihood implementation for the farmers” – especially in the Helman region, which used to produce 80% of the total opium production. Farmers try to resist the change but are suppressed by the Taliban.

Revisiting the past: what could have been done to prevent the downfall into autocracy?

Arian recalls the situation back in mid-2021, when the Republican government was still holding power over “31 out of 34 provincial capitals”. President Ghani told our expert about many security, military, and management issues that prevented them from sustaining the fight against the Taliban, and asked him what could be done. Sharifi strongly suggested negotiating with the group and working towards proving to them and the population that the Republic could implement reforms for higher security and boost the economy.

For Sharifi, the faux-pas was made when the Republic chose to focus solely on the capital, Kabul, which represents only about 20% of the whole Afghan population – he made a “population-centric defence strategy” including the advice to allocate military forces to 8 to 9 provinces (Kabul included) representing 70-77% of the population, and recommended building three main highways connecting these provinces to the outside of the country. This plan aimed to show the Taliban that the military men could sustain a year of physical and efficient presence without the help of the U.S., a plan which was never adopted. Furthermore, our expert assesses the morale, trust, and will of the Afghan forces as very low at the time.

A warning to the Taliban: how to achieve a sustainable state through political and infrastructure reforms

Arian Sharifi believes that the majority of Taliban leaders understand their actions to be unsustainable and start believing in the necessity of reforms. Moreover, he suggests starting with the establishment of a Constitution, ensuring the basic rights of citizens, and aligning with the Sharia and “Afghan traditions” – reflecting the population’s predominantly “very religious and traditional” values.

Finally, the sharing of power with technocrats seems crucial for future reforms to create durable institutions. Dr. Sharifi says the Taliban unanimously refuse to share power with financially powerful individuals. However, members residing in Kabul are open to the idea of opening political decision-making to “technocratic Afghans”; the problem is that Kandahar, whose supreme leader is Mullah Hibatullah, is opposed to any reform. According to our guest, a change of heart from the leader would impel change, but there is no guarantee this would happen any time soon.