Speaking to both Petra Molnar and Lori Wilkinson in our recent episodes about refugees and the vast array of issues impacting them on a daily basis has, I’m sure, made us all far more aware of quite how profoundly every facet of a refugees life is impacted upon entering a ‘safe’ state, otherwise known as a host country. It is estimated that there are around 36.4 million refugees worldwide. Only 24% of these people seek refuge in a high income country. The risks facing refugees are vast, from often being displaced for years at a time, to facing significant discrimination and marginalisation when seeking safety in another country. One of the key issues raised in Lori Wilkinson’s episode was that of underemployment, and a key systematic issue within states including Canada, that prevents refugees from gaining work they have the qualifications for. This article will therefore focus on this phenomenon, and examine what reforms can be made to mitigate the risks of this underemployment epidemic persisting in the future.

What Is Underemployment?

Underemployment serves as a measure of the number of people in an economy who are working in low-paid or part-time jobs because they can’t find a job that matches their skills. In Europe for example, migrants with tertiary education experience huge difficulties in finding employment, and many find themselves ‘working in a job that is below [their] full working capacity than workers born in the host country’. Not only is this detrimental for a refugee’s future within a host country, but it can also be disastrous for the host country itself. States, such as Canada, suffering a shortage of vets, for example, will continue to struggle to fill the gap in the market for trained vets, despite hosting a host of migrants who are fully trained and capable of filling the void left in the market. The same logic also applies for dentists, doctors, and a whole host of other professions. So the question remains, why is there such a large underemployment epidemic in host countries?

The Issues Impacting Migrant Employability

According to Kelly Clements, the Deputy High Commissioner for Refugees at the UNHCR, one of the main challenges faced by refugees is their limited access to the formal labour market. ‘Language barriers, lack of recognition of their qualifications, and discrimination all limit job opportunities’ Clements said to the World Economic Forum. As we heard from Lori Wilkinson, when refugees are given little to no time to flee their houses, under threat of arms and hostile groups, many do not have the opportunity to retrieve certificates, or evidence of qualifications. In warzones in particular, many schools and universities cease to exist and with it goes the qualifications gained by those who attended them. Even those with evidence of their qualifications are left, in many cases, unable to work in their qualified profession due to not being trained in the host country. Consequently, thousands of qualified doctors, nurses, dentists, vets etc end up forced to work in jobs far below their skill levels, for example, as a taxi driver or construction worker, adding to the underemployment problem.

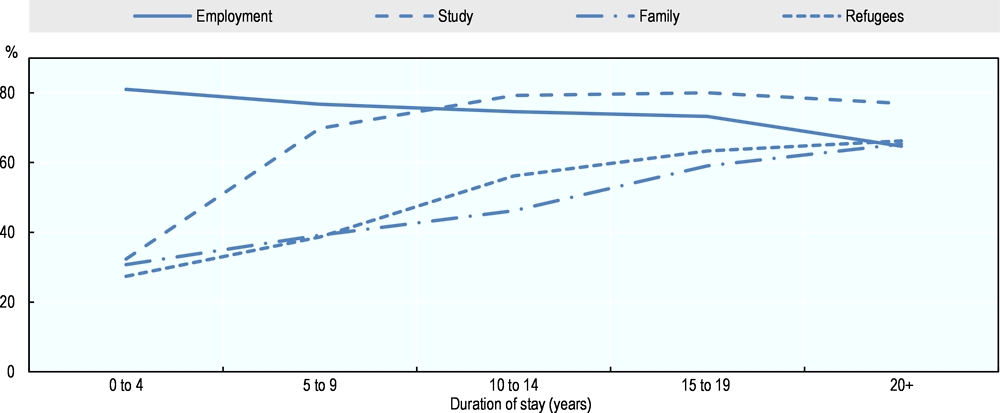

Those who become refugees at a younger age suffer huge disruptions to their education. Many spend up to 7 years in a refugee camp, entering a host country with huge language challenges, and behind in educational qualifications. This along with an absence of social and professional networks makes it almost impossible to successfully enter the job market, leaving both unemployment and underemployment rampant in host states.

The Importance of Having Refugees in the Job Market

There are thousands of studies that show how the inclusion of refugees in the job market revolutionises both workplaces, through their hard working attitudes and state economies through increasing economic inclusion within host states. As the UNHCR states ‘access to employment and entrepreneurship enables refugees to contribute to their host economies as consumers, taxpayers and employers’. Key arguments against resettling refugees into a host state include the cost of resettlement (up to $15,000 per person in the United States); the long term economic benefits of resettlement far outweigh any initial costs.

These benefits go far further than economic, however, as refugee assimilation brings with it vast swathes of cultural enrichment, diversity and increased socialisation. As we heard in Lori’s episode, whilst this isn’t something measured or accounted for in our post-Washington Consensus capitalism based Western society, it remains something that is nonetheless crucial for the sociological advancement of societies.