Grey Zones at Europe’s Edge: Ceuta, Melilla and Maritime Power

How two small Spanish cities on Africa’s coast expose bigger problems in migration, sovereignty, and maritime power

Ceuta and Melilla embody anticonformism in the geopolitical order as two beautiful Spanish cities situated on the African continent. Yet they sit at the centre of Europe’s most complicated border politics. In practice, they are more than enclaves: they are part of a strategic game that combines migration control (with physical borders), diplomatic bargaining, and maritime rivalry shaped by legal anomalies created over 500 years of history. Drawing on Ángeles Jiménez’s insights as a Lawyer and Maritime Law specialist, and on facts, this article explains why these two places matter far beyond their size.

This is a case study in how “non-war” tools (people flows, legal claims, port access, trade friction) can be weaponised to shape outcomes, and how critical maritime geography turns border politics into supply-chain and infrastructure risk. For most business and political leaders, Ceuta and Melilla may sound like a footnote: two small Spanish enclaves on the North African coast, occasionally in the headlines for migration surges. The real story is that they sit on a political fault line, which makes them useful as leverage in greyzone warfare and international risk. When pressure is applied there, it spills into geopolitical drama, diplomatic bargaining and trade offs, border policy, shipping routes, and commercial confidence. Ceuta and Melilla show how border management and migration flows are actually strategic signals we must pay attention to.

A long, politically tricky history

Grey Dynamics, Ceuta and Melilla: Spain’s Overseas Territories in Morocco Disputed? Iñigo Camilleri De Castanedo, April 15, 2021

Ceuta and Melilla have been under Spanish control since the 16th century, and their modern borders were consolidated in the 19th century by treaties such as the 1860 Treaty of Wad-Ras that followed the War of Tetouan. Today, both enclaves are Spanish “autonomous cities” under the 1978 Constitution, with special customs and fiscal arrangements that set them outside the EU customs union and VAT regime, but being part of the Schengen area, the travel requirements are customised to represent EU controls. That mix of special local rules and the EU mandate is what makes them unique and surrounded by debate.

Ángeles Jiménez points out this legal and geographic blend. Because the enclaves sit at the Strait of Gibraltar, an area which is governed by many outside interests (the EU, the UN around Western Sahara, the UK because of Gibraltar, and U.S. naval presence at Rota), their fate is influenced far beyond bilateral Spain-Morocco ties. Although the law of the sea and the law of territory matter, the true representation of Ceuta and Melilla is that of a melting pot of Sephardic Jews, Roman Catholics, Hindu Indians, Berber Amazighs, British, and Muslim communities whose culture, cuisine, architecture, and language remain present on the ground.

Therefore, the enclaves are normal cities with blended cultures and economies led by Spanish administration, and residents of neighbouring Moroccan provinces have specific border privileges, but fences and visa rules create a clear discontinuity from mainland Spain. That is precisely why mass attempts to cross produce crushes, use of force, and delayed medical access when things go wrong -all failed state-likeness which grey-zone actors can exploit.

External EU borders turned into geopolitical leverage

Source: WordPress.com, The fence: between a world of need and a world of excess, Gerry in Ideas and Politics. October 24, 2014. Image description: A Melilla fence ends in the Mediterranean at the border between Morocco and the Spanish enclave

Because these cities are the only land borders between the EU and the African continent and the easiest access from one to the other, they have become key places for Europe to externalise migration control: the EU has provided more than 270 million euros since 2007 to support Moroccan border control, €148 million in 2019 alone, creating incentives for the kingdom to maintain its role as a “reliable partner”. In 1985, in preparation for their joining the EU (at the time the “European Communities”) in 1986, Spain implemented the Ley de Extranjería, a restrictive law maintaining police control over migration. Fences, cameras, and dual Spanish/Moroccan patrols now guard the gates where thousands have tried to force entry in recent years. In 2012, a treaty reinforced the cross-border police collaboration between Tangier and Algeciras to “fight irregular migration and trafficking”.

However, when Spain admitted Polisario leader Brahim Ghali -leader for the independence of the Western Sahara from Morocco- for medical treatment in April 2021, Morocco reacted in a way many observers read as political pressure: about 6,000 people crossed into Ceuta in mid-May 2021 in a single wave.

The human cost was huge: on 24 June 2022, over 2,000 migrants tried to cross into Melilla, leading to clashes at the Barrio Chino crossing and between security forces and migrants. Dozens died (Human Rights Watch documented at least 23 fatalities and called for an independent inquiry), hundreds were injured, and some people were declared missing. NGOs and investigations since then have framed the episode as the direct consequence of highly militarised borders and politicians’ reprehensible tactics. This episode showed that migration can be mobilised as leverage in international relations.

Grey-zone tactics: subtle disputes, not yet war

Morocco World News, Morocco Affirms Dialogue-First Approach in Maritime Border Talks with Spain Adil FaouziByAdil Faouzi, August 28, 2025. Image description: “Morocco’s Foreign Affairs Minister, Nasser Bourita, and his Spanish counterpart, José Manuel Albares.

“Grey zones” describe offensive statecraft not indulging in armed conflict, taking forms like economic pressure, diplomatic manoeuvres, controlled migration waves, or even legal moves to reframe borders. Jiménez highlights several practical grey-zone techniques Morocco has used or tried to act on: closing trade crossings (during a ban on European products’ flow into Morocco through Melilla in 2018), diplomatic escalation, and legislative or administrative acts that assert maritime claims. Ceuta and Melilla are widely seen as grey-zone theatres where sovereignty and governance are ambiguous, and pressure is carefully applied by Morocco: occasional decisions at the border can look like intentions to obtain political concessions from Madrid without triggering a military crisis.

The pattern has historical precedents: the 1975 Green March, when Morocco mobilised unarmed civilians to press Spain over Western Sahara’s sovereignty, is a historic example of mass mobilisation as strategic leverage. Today, the country mixes legal acts with migration and economic measures -in 2020, Moroccan domestic laws incorporated Western Sahara waters into national maritime frameworks, knowing that seabed and EEZ -Exclusive Economic Zones- claims overlap with Spain’s interests (notably around the Canary Islands).

Maritime stakes: the shelf, seamounts, and strategic minerals

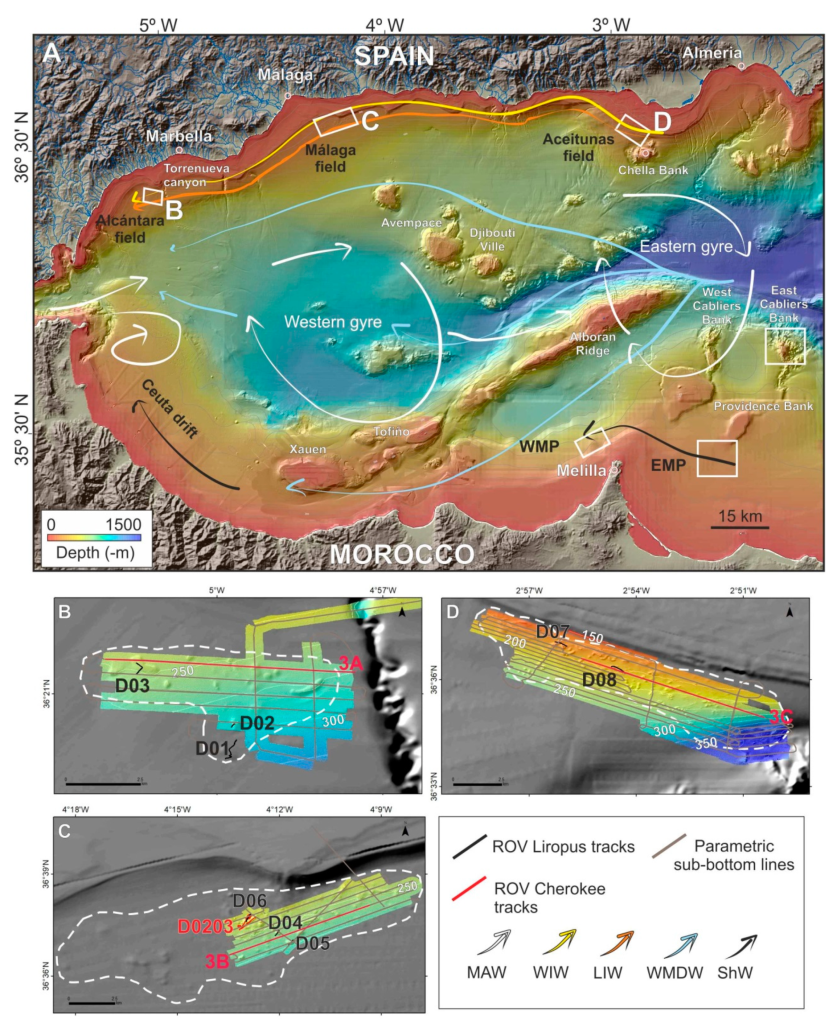

MDPI.com Geophysics, Morphosedimentary, Structural and Benthic Characterization of Carbonate Mound Fields on the Upper Continental Slope of the Northern Alboran Sea (Western Mediterranean), Image description: “ (A) Overview map showing the three carbonate mound fields (B–D) on the northern margin of the Alboran Sea described in this study and the location of cold-water corals (CWC) mound provinces detected in the southern Alboran Sea. (C) Málaga carbonate mound field and (D) Aceitunas carbonate mound field showing the location of dive tracks and sub-bottom parametric profiles (lines). Extension of the mound fields are marked by white dotted contours. The black scales represent 2.5 km. Bathymetric contours with 25 m spacing are shown as white lines.”

The legal fight isn’t only about cities: it reaches into the deep sea. Spain filed a partial submission to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) in 2014 for the area west of the Canary Islands, claiming natural prolongation and historical sovereignty; Morocco has adopted domestic laws that assert maritime zones -including waters adjacent to Western Sahara-, that could affect Spain’s and other European countries’ rights to seabed minerals, fisheries and critical subsea infrastructure –like oilfields. The technical process before the CLCS is slow, but it matters: whoever secures legal recognition over a shelf or EEZ gains exclusive resource rights and leverage in any future deals. Jiménez, who has researched Spain’s continental-shelf claims in depth, warns that competing submissions and political protests can stall or freeze outcomes for years, converting a technical procedure into a broader, geopolitical issue which could lead to conflict.

What would meaningful responses look like?

The policy implications are complex and involve many actors. The first action could imply de-escalating instrumented migration: Spain and the EU would need to reduce incentives for state-level manipulation by combining predictable migration pathways with jointly-managed readmission agreements that protect people. The 2013 EU-Morocco mobility partnership and EU funding to support border management show what cooperation can look like -but funding must be paired with transparency and independent management.

Moreover, it is important to depoliticise investigation and promote accountability by allowing an independent search into deadly border incidents (like Melilla 2022) to reduce mutual accusation and prevent propaganda. Human rights groups have repeatedly demanded impartial inquiries, a moral and strategic necessity.

Finally, maritime technicalities should be separated from political rivalry: the CLCS process and continental-shelf science, critical to economies and the advance of science, mustn’t be subjects of disputes. Where an overlap is unavoidable, like in the case of Ceuta-Melilla, negotiated provisional arrangements (like joint development zones, technical commissions) can preserve coastal communities and prevent contests over seabeds from spilling into war. Left unaddressed, these tiny cities will continue to mirror Europe’s fragile border strategy depending on risky grey-zone dynamics