On 25 September the Italians were called to vote for the election of the new parliament. After the resignation of Mario Draghi, having lost support within the coalition in Parliament, he left the country at a turbulent and time of high risk. As said by Giovanni Capoccia during his interview on The International Risk Podcast, “the last five years have seen three different governments in Italy.”

Since the beginning of the election campaign, the centre-right coalition formed by the Brothers of Italy of Giorgia Meloni, Lega Nord of Matteo Salvini and Forza Italia of Silvio Berlusconi have been considered from the beginning as the winners.

Within their election campaign they immediately tried to firmly affirm their principles, such as those concerning the issues of birth, carrying forward with them values such as the “natural family”, which is described as composed of father and mother, the semi-closure of national borders to migratory flows and a foreign policy based on “the defence of the homeland”, which some have described as an international risk.

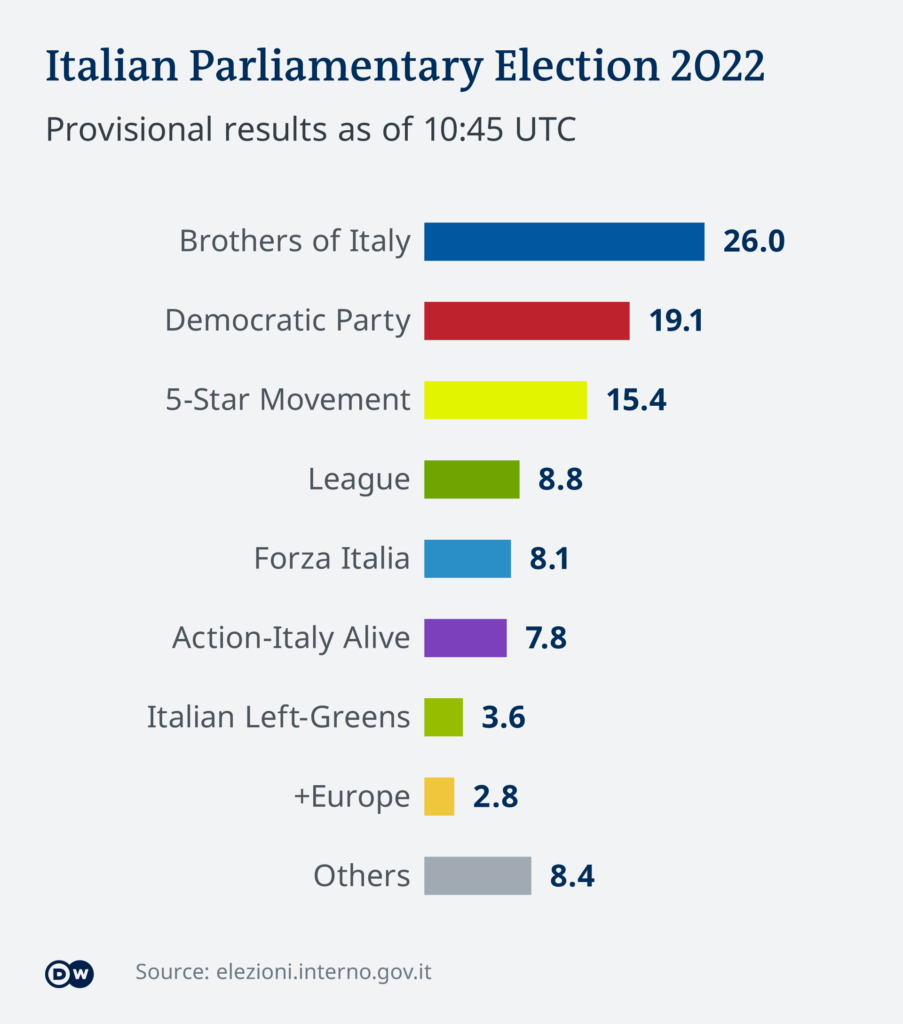

According to Italian Government data, reported on September 26, to have established itself as the first party is the Brothers of Italy of Giorgia Meloni, with over 26 percent of the vote. The election in Italy has been closely watched in Brussels and Washington, where policymakers are anxious about what the new government will mean for Rome’s relationship with the EU and Italy’s approach to the war in Ukraine – all important topics for ensuring stabilization in a time of persistent volatility and high risk internationally. As stated by the Financial Times, Meloni and Salvini “have fiercely criticized the EU — Meloni has called Brussels bureaucrats agents of “nihilistic global elites driven by international finance” — and both flirted with leaving the euro, though they have lately muted their hostile rhetoric”.

What happens now after they win? Some clues had already been suggested to us from the beginning, from the election campaign that called for respect for “God, family and traditions”. Civil rights, especially for those in the LGBTQ+ community, that endanger families by destroying the “gender identity”, and for women, will be increasingly restricted and the lives of millions of refugees and migrants, who are only looking for a better life, will simply be put at greater risk, accentuating the naval blockade, thus preventing them from entering and continuing to carry out a campaign of “first the Italians”.

In a different situation, the country would celebrate the victory of a probable next first female minister as a huge event, but this does not happen when it is a woman who takes away fundamental rights for women. Within days of her victory, the right to abortion is already in danger. Giorgia Meloni immediately stated that she did not want to abolish or amend Law 194, which includes a series of rules for the social protection of maternity and voluntary termination of pregnancy. And it is true: it is not necessary to delete or amend this law to prevent access to the right of abortion in Italy, because it is so imperfect and workable that in any case, Giorgia Meloni manages to achieve her goals. In fact, in all regions of Italy, it is not access to abortion that is lacking, but rather who is not an objector and who does not refuse to practice this, preventing in any way to lead to an interruption of pregnancy. As Politico reports “as it currently stands, in order to obtain an abortion, Italian women must undergo a medical examination, observe a seven-day waiting period and sustain a mandatory counseling session aimed at helping remove “any obstacles” to carrying the pregnancy to term”. It seems that a woman does not have the opportunity to choose for herself, but on the contrary, it is the State, who makes her decision and shatters her rights.

These are just some of the many reasons why the country could return to an era that it had long sought to forget. Moreover, to make even more understand the gravity of the situation, as well as reports the Guardian, “Meloni was reportedly merely a teenager when she praised Italy’s second world war fascist leader Benito Mussolini”.

Fascist symbols can also be found in the logo of Fratelli d’Italia, including the flame, which recalls these dark days.

At the expense of this, Giorgia Meloni was sent a few weeks before the election by Senator Liliana Segre, a Holocaust survivor, to remove the symbol that has so persecuted us for a long time, but without getting any results.

It is therefore obvious that this party, and its allies, call for an extreme right-wing and not centre-right movement, as defined by all Italian newspapers. The election campaign shown in recent months shows everything, except that the parties coalesced right to bring optimism and loyalty to the rule of law.

All that has been advertised and shown reminds us of the dark and dark times that Italy, as a country, has always tried to erase. Unfortunately, however, the people, who hold in their hands the right to vote and to be able to finally change things for the better, are not of the same opinion and the country will soon recreate in its obscure past.