Pakistan Underwater: A Tumultous Summer of Floods and Rising Uncertainties over the Indus

Pakistan has been battling severe monsoon flooding this year, enduring almost constant flooding since June. The devastation has been calamitous. According to the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), since the rains began on 26 June, 998 deaths have been reported. Torrential rains and riverine flooding wreaked havoc across the country’s agricultural heartland: over 4,700 villages have been submerged, crops and homes destroyed and hundreds of thousands displaced. The Pakistan Senate reports that at least four million people have been affected and 300,000 remain in tents. No region has been spared but Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, followed by Punjab and Sindh, has been the hardest hit.

The worst spell came in mid-August when Khyber Pakhtunkhwa witnessed 150mm (6 inches) fall within a single hour. Between 15 and 17 August alone, 313 were killed and over 100 were missing as monsoon rains triggered sudden cloudbursts, flashdloods and landslides. Swollen rivers and mudslides swept away entire villages. In Bishnoi, a town in the Buner district 100km from Islamabad, half of the houses were completely destroyed while the rest were left uninhabitable. Just days later, a glacier lake outburst flood (GLOF) in Gilgit-Baltistan blocked the Ghizer River, resulting in a deadly downstream rush that killed 200 people. By early September, even the vibrant streets of Karachi lay underwater.

However distressing the news has been for Pakistanis, these were not freak incidents but part of a recurring annual pattern that is only intensifying. The August floods triggered memories, or better said nightmares, of the cataclysmic floods of 2022, when Pakistan experienced its worst monsoon season on record: 1,700 people were killed, 8 million displaced and damages exceeded $40 billion.

Geographic Vulnerabilities and a Changing Climate

Pakistan’s geography makes it particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The country faces not just heavy monsoon rains, but also extreme heat, drought and the rapid melting of glaciers that are worsening due to global warming.

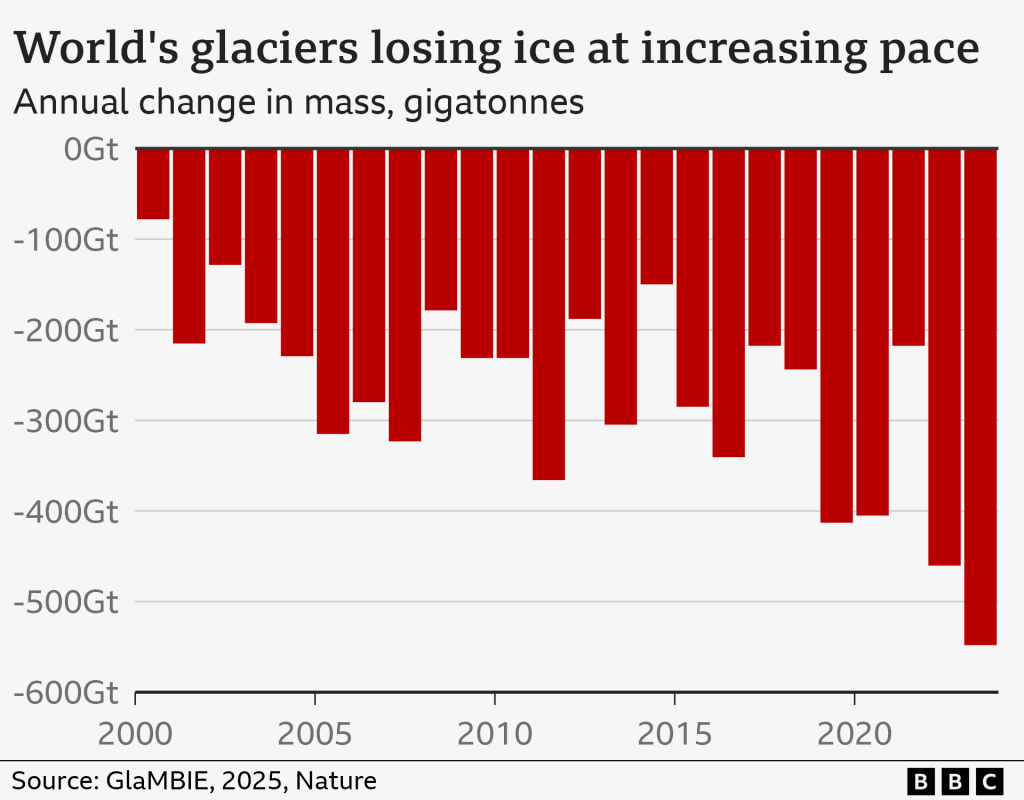

Monsoon season, lasting usually from June to September, brings roughly three-quarters of South Asia’s annual rainfall, with August as its peak month. But with climate change presenting more volatility, altering rainfall patterns and glacial melt in the Himalaya-Hindu Kush region accelerating, Pakistan’s risk landscape is being transformed. The country is home to over 13,000 glaciers—in fact, this is the largest concentration outside the polar regions—and record-breaking summer temperatues, reaching 48.5°C this year, have accelerated melting, contributing to more intense flooding. “Pakistan is a hotspot for increases in extreme rainfall” and is “undoubtedly on the front line of climate change,” says Friederike Otto, a climate scientist at Imperial College London, and founder of World Weather Attribution, an international collaboration assessing the causes of extreme weather events.

There is also the issue that Pakistan is positioned downstream of India on the Indus River system. As Dr Erum Sattar, speaking on The International Risk Podcast, observed, “it’s always the upstream country that has first access to water”. With the majority of Pakistan’s renewable water resources coming from the Indus, the country’s dependence on external water flows is an additional geographical vulnerability. This power dynamic plays out not only on the state level between India and Pakistan but also across Pakistan’s own provinces, deepening internal water disparities.

The India Factor

While heavy monsoon rainfall was the main driver of this year’s floods, they were exacerbated by excess water released from Indian dams. Intense rain in Indian Punjab caused the Ravi, Chenab and Sutlej rivers to overflow, prompting India to discharge reservoir water downstream, only aggravating the flooding on Pakistan’s side.

This has come at a time of heightened uncertainty. Earlier this year, India unilaterally suspended the Indus Water Treaty amidst the worst fighting between the two nuclear-armed neighbours in decades. The move was significant. Having been honoured peacefully for over 60 years, withstanding multiple wars, nuclear tests and diplomatic breakdowns, India’s decision to put the Treaty in abeyance marked the first time that tensions had disrupted the water agreement. India’s actions since the suspension have also marked its first tangible steps operating outside the treaty’s framework, including curbing the Chenab River flows—one of the Western rivers that the Treaty gave Pakistan exclusive control over—reportedly by up to 90% and conducting sediment flushing at its Salal and Baglihar dams. Although India shared flood warnings in August with its downstream neighbour on humanitarian grounds, one of the most concerning impacts of the Indus Water Treaty’s suspension is that India has ceased routinely sharing hydrological data, sharply reducing Pakistan’s future flood preparedness and mitigation capacity.

Moreover, as Dr Sattar astutely noted, “the treaty doesn’t at all say you can suspend it”, raising serious legal questions about the legality of India’s unilateral decision to suspend the Treaty. Pakistan has been pressing its legal claims in international fora, including at the Hague, but India has refused to appear in front of these courts, rejecting their jurisdiction. Sattar stressed that ” this is a problem because it completely breaks down bilateral communications between the two countries”.

India’s leaders have instead adopted increasingly inflammatory rhetoric. Home Minister Amit Shah vowed that “Pakistan will be starved of water” while Water Minister Chandrakant Raghunath declared on X, ” we will ensure no drop of the Indus River’s water will reach Pakistan”. Water politics experts such as Filippo Menga have argued that India’s actions reflect a growing erosion of international law and a surge in unilateralism. Regardless of whether India’s decision to put the Treaty in abeyance is ruled legal or not, its unilateral move without due process undermines the core principle of pacta sund servanda codified in Article 26 of the Vienna Convention: treaties must be honoured in good faith.

Ripple Effects on Public Health, Food Security and Migration

The suspension of the treaty, coupled with the recurrent floods, has dire implications for public health and food security. Health workers this summer have reported surges in malaria, fever and skin infections as floods contaminate already scarce water supplies. Waterbone diseases—already responsible for roughly 80% of illnesses in Pakistan, including hepatitis, diarrhoea and cancers, and a leading cause of death and childhood stunting—are expected to surge further.

Even before the suspension and without considering climate change-induced flooding, Pakistan struggled to provide safe drinking water. Dr Sattar described Pakistan’s public health as a “really, really, big complex problem”. While most citizens technically have access to water, only 36% is safe to drink. Whenever Dr. Sattar visits Pakistan, she speaks to locals about how they source their water. Many, she observed, do not boil it; not out of neglect, but because it is seen as too costly. Boiling water requires energy, which then becomes an additional expense, and in a country where nearly 45% of people live below the World Bank’s poverty line and 16% in extreme poverty, many simply cannot afford it. “They just drink what’s available,” Dr Sattar said.

This willingness to consume whatever water is accessible reflects how water insecurity, public health and poverty are deeply intertwined. The inability to afford safe water or fuel to purify it traps communities in a cycle of preventable disease and vulnerability, which climate change and poor infrastructure only exacerbate. Similarly, the poorest households, often settled along riverbeds, find themselves repeatedly displaced by floods and at the frontline of the water crisis.

Agriculture, too, is under severe threat. The Indus Basin forms the backbone of Pakistan’s agricultural sector, employing nearly 40% of Pakistan’s workforce and contributing about a quarter of GDP. With over 80% of farmland reliant on Indus irrigation, erratic flows, especially in light of the suspension, could destabilise food production. As Head of Production at Pakistan Agriculture Research noted, “If water flows become erratic, the entire system takes a hit, especially irrigation-dependent crops. Yields could drop, costs could rise, food prices would likely spike and small-scale farmers, who already operate on thin margins, would bear the brunt”.

Compounding this is a deepening groundwater crisis. About half of Pakistan’s irrigation water comes from underground aquifers, which are being extracted faster than they can sustainably recharge. Unlike surface water, there is no treaty or national framework to govern groundwater extraction. As Dr Sattar cautioned, “the groundwater crisis around South Asia is only going to become worse, which is going to make food production more costly”.

The combined pressures of climate change, upstream animosity and groundwater depletion raise troubling questions about the future habitability of the Indus basin and the uncomfortable reality that few governments are prepared to face, especially in a world increasingly hostile to migration, with rising anti-immigration politics: where will people go when their lands can no longer sustain life?

Governance and the need for better climate resilience

Pakistan ranks among the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries. Yet, it also remains one of the least prepared. The Notre Dame Global Adaptation Initiative ranks it 150th out of 192 for disaster readiness. As Karachi-based climate advocate Afia Salam put it, “the rapidity of these events is increasing and our response is not keeping pace”.

Poor institutional coordination, inadequate early monitoring systems and ageing, fragile infrastructure exacerbate disaster impacts. According to NDMA, nearly 30% of deaths this monsoon season resulted from houses collapsing. Building resilience will require serious governance reform. Expanding early warning networks, investing in nature-based flood buffers such as forest restoration, upgrading climate-resilient infrastructure and improving public communication, particularly in rural and mountain areas where connectivity is limited, are all solutions that have been proposed.

Above all, Pakistan must reckon with its national priorities. Despite the clear and mounting costs of climate inaction, climate adaptation remains chronically underfunded and treated as secondary. Amid overall budget cuts this year, the Ministry of Climate Change’s allocation was reduced to just $9.7 million while defence spending rose to nearly $9 billion. Pakistan must recognise that climate change is not a distant challenge but one of its biggest national security threats.

Faced with economic instability, Pakistan will also need far more international assistance. Without systemic change in water governance and disaster management, this cycle of devastation will only intensify. Pakistan cannot change its geography, but it can take steps to strengthen its resilience and adaptability in the face of a changing climate.