France at the Crossroads: Debt, Politics, and Taxing the Ultra-Rich

In this episode of the International Risk Podcast, Dominic Bowen is joined by Susannah Streeter to examine the pressures weighing on France’s economy, from credit downgrades and long-running deficits to a political landscape that struggles to deliver coherent fiscal reform. Their exchange explores how these domestic challenges shape Europe’s wider financial stability, raising questions about investor confidence, the credibility of EU rules, and the chain reaction of legislative paralysis in one of the bloc’s largest economies. Susannah Streeter is a leading financial expert, international broadcaster, and former BBC business anchor who explains global economic, technological, and geopolitical trends to audiences worldwide. Former head of money and markets for the UK’s largest retail investment platform, Hargreaves Lansdowne, she now speaks and moderates at major global events, interviewing CEOs, world leaders, and policy-makers in both English and French. A former RAF Squadron Leader, she brings sharp strategic insight to her analysis, appears across major media outlets, hosts top-performing podcasts, and writes regularly for The Evening Standard and City AM.

Economic Fundamentals Under Pressure

Susannah Streeter warns that France’s economic and fiscal vulnerabilities and the political risk facing the country cannot be looked at separately. It is precisely this combination of powers that markets are watching closely.

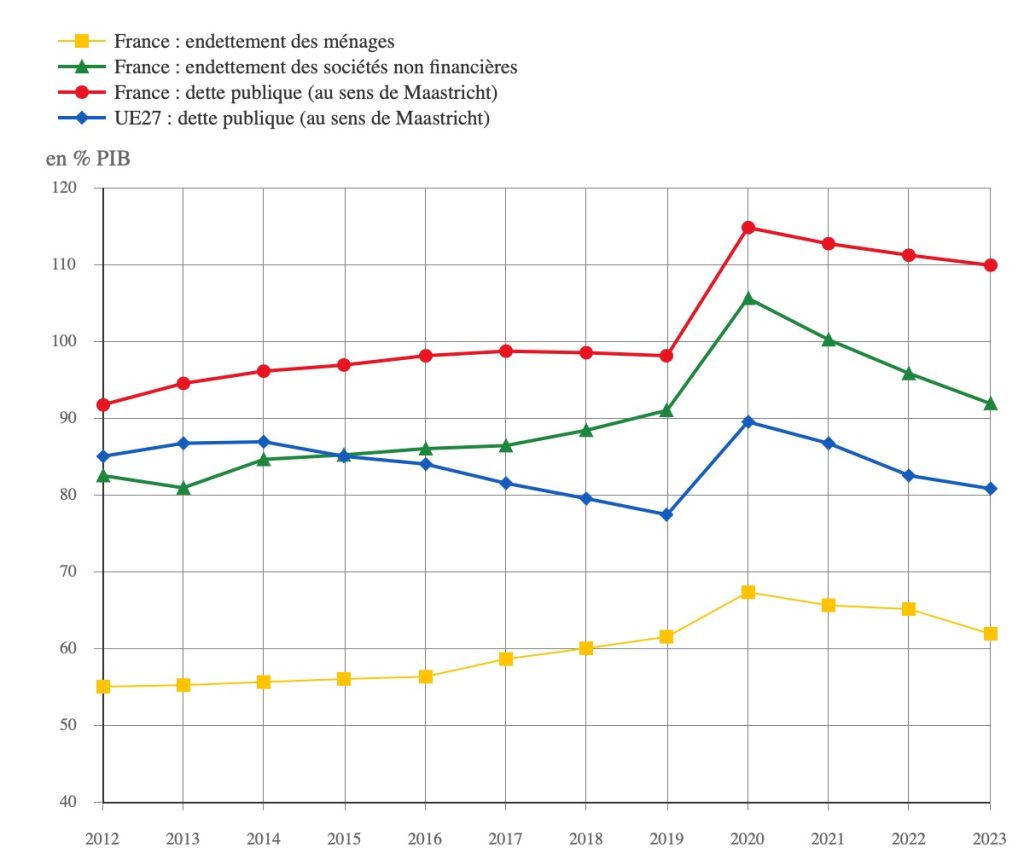

According to the latest data from INSEE, France’s public debt stood at €3,345.4 billion at the end of 2025’s first quarter of 2025 -roughly 114% of GDP. By the second quarter, that figure had climbed further: INSEE reports 115.6% of GDP, with gross debt rising by €70.9 billion in just a few months. Meanwhile, the general government deficit remains large: in 2024, it was 5.8% of GDP -about €169.6 billion.

This debt trajectory illustrates why markets are concerned: not only is debt high, but it’s still accelerating, which makes any credible financial commitment very challenging – especially in a very unstable political environment.

Political Instability: A Drag on Confidence

Streeter repeatedly links political fragmentation in France to its fiscal risk. Her point: without stable governance, meaningful reforms are very hard to pass. She observes a few things: first, that the fall of François Bayrou’s government and the rise of Prime Minister Sébastien Lecornu happened during a volatile fiscal moment. Agencies like Fitch explicitly cited “instability” and “fragmentation”. Fitch’s September 2025 downgrade followed the government’s collapse and questioned whether there were any “clear horizon for debt stabilisation in subsequent years.”

Susannah also emphasizes how difficult cross-party compromise is in France, compared to other European systems, making bold fiscal reform unlikely in the near term. The political instability thus doesn’t just look bad; it is a direct input into France’s worsening credit risk.

The Fitch Downgrade and Market Reaction

On September 18th, 2025, Fitch downgraded France’s long-term sovereign rating from AA- to A+. The renowned ratings agency said that despite France’s size and economic fundamentals, the lack of a “credible medium-term fiscal consolidation plan” justified the cut. Critics have noted that the downgrade was mostly already priced in by markets, as France’s borrowing costs had been rising before the announcement.

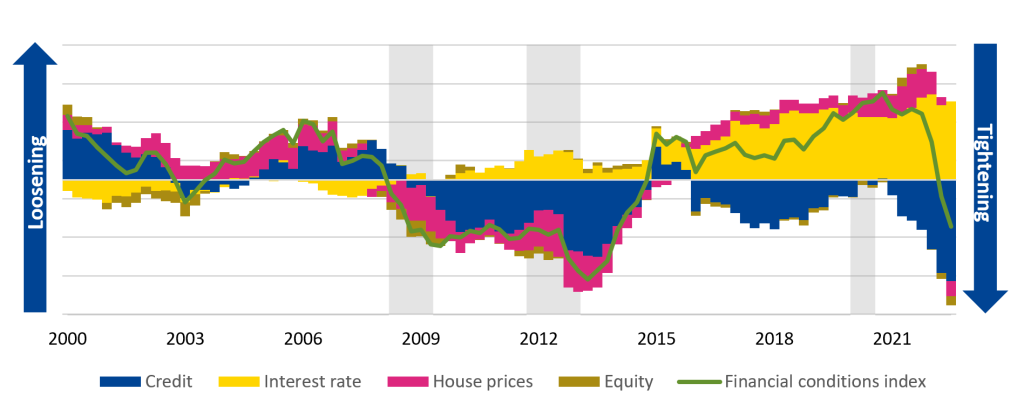

So, does this downgrade really matter? In some ways, it does. First, it leads to higher borrowing costs: as credit risk rises, investors demand more yield, which is the return (interest) investors earn from a bond.

Moreover, France could be faced with more regulatory constraints: some banks or funds may face and even impose limits on holding lower-rated government bonds. On France’s side, the Ministry of Finance would possibly shift its funding strategy, issuing more short-term debt as long-term issuance becomes more expensive or risky.

Streeter emphasizes the mechanics of this risk: if investors lose appetite for long-dated French debt, Paris could be forced to rely more on short-term borrowings, which increases “rollover risk” (i.e., the risk that it will be more expensive to refinance long-term debt).

Defining Key Financial Concepts

For our readers to understand these issues, a few definition to clarify technical terms:

- Sovereign Credit Rating: An evaluation by agencies (like Fitch, Moody’s, S&P) that reflects a government’s risk of defaulting on its debt.

- Budget Deficit: The amount by which government spending exceeds its revenues in a given year.

- Debt-to-GDP Ratio: A measure of a country’s public debt relative to its annual economic output.

- Rollover Risk: The risk a borrower faces when issuing or refinancing short-term debt -which is especially dangerous if market conditions deteriorate.

- Yield Spread (or credit spread): the difference in yield between two bonds -often used to compare risk (e.g., French 10-year vs German 10-year return on interest). A wider spread means investors demand more to hold the riskier bond.

The Zucman Tax Debate: Taxing the Ultra‑Wealthy

One of the central political-economic flashpoints that Streeter returns to is the Zucman tax, a proposal by economist Gabriel Zucman to impose a 2% annual tax on assets over €100 million. The goal is to ensure the ultra-rich pay at least 2% of their net wealth in taxes, correcting what supporters see as a distortion: many of these individuals have large unrealized gains that are not taxed under current rules.

The Zucman team pushed for the tax to be adopted -before it was rejected by the National Assembly on October 31st – by putting forward multiple arguments, notably that of generating large revenues, suggesting estimates of €15–25 billion annually. They also addressed the inequality at the base of the proposal, saying it is partly caused by the fact that the wealthiest pay proportionally less in effective tax rate (due to the structure of their assets). Finally, the proposal reflected on restoring progressivity, by taxing unrealized wealth and not just income.

However, criticism flowed in response to Zucman’s grand reform ideas. First, the argument of valuation issues was largely put forward: assets like private company shares or complex financial instruments are difficult to value fairly. Next, many politicians and financial experts warned about the “capital flight”, saying that high-net-worth individuals may relocate to avoid the tax unless similar reforms happen globally. Finally, critics suggest that the tax would reduce investment and entrepreneurship.

Streeter notes that such a tax, if implemented unilaterally, is risky and would need international coordination to be effective without driving away capital.

International Tax Coordination & BEPS

A key piece of Streeter’s analysis is that real progress on taxing the ultra-rich must happen through multilateral frameworks, not just nationally. Here, the OECD’s BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) Project comes into play. BEPS refers to strategies by multinational companies to shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions, eroding national tax bases. Part of the BEPS initiative includes a global minimum tax: the GloBE rules (or Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules), which ensures large multinationals pay at least a certain effective tax rate internationally. If France wants to tax wealth and capital effectively, doing so in isolation makes it vulnerable on the international financial markets; working within global frameworks reduces that risk.

What financial expert Susannah Streeter stresses is that a “wealth tax battle” wouldn’t just be about France, but about rethinking how global tax systems deal with ultra‑rich and mobile capital.

Broader Risks: Geopolitics, Markets & Safe Havens

Beyond fiscal risk, Streeter warns of geopolitical shocks that could deepen financial pressure: China–Taiwan tensions or supply‑chain disruptions could for example force Europe to spend more on defense, adding to fiscal strain. Of course, the Ukraine war remains a drag on European cohesion and budgets, reminds us the expert.

Moreover, the Arctic faces great challenges: melting ice, resource competition, and new trade routes, presenting strategic and economic risks in the medium to long term.

Commenting on financial markets, Susannah also touches on how investors are recalibrating. According to her, there may be a general wave out of riskier assets toward safe havens like gold, especially if European debt looks riskier than U.S. assets. Finally, she does suggest that higher yields in France could attract some investors, but only if political risk stabilizes -otherwise, the “risk premium” may just go up more, she warns.

What to Watch Going Forward

Based on Streeter’s line of reasoning, three key metrics will be critical in the short-to-mid term. First, the 2026 French Budget: how realistic is the government’s plan for reducing the deficit? Will they propose credible cuts or rely on tax increases? Can they secure parliamentary support? Second, rating Agencies’ actions: will S&P or Moody’s issue downgrades or outlook changes? A further downgrade would certainly intensify pressure. Furthermore, Susannah recommends watching the market funding dynamics, how spreads go, the composition of debt issuance (short versus long maturity), and the demand from international investors.

If France can deliver on some of its commitments, markets may stabilize. But if political fragmentation continues, investors may demand ever-higher yields, raising the cost of debt for the French state, inflicting further immeasurable strains on French workers.

Why This Matters Beyond France

Streeter’s core insight is that France’s economy is not just circulating within, but is a European systemic risk. Because of its size and integration in the euro area, fiscal stress in Paris can spread across the continent: credit rating downgrades, rising yields, and funding instability in France could have a domino effect on other European issuers and countries, and test the resilience of the euro area.

At the same time, the debate over taxing the ultra-rich is part of a global conversation. How France handles this could influence multinational discussions and coordination at summits on tax, inequality, capital flows, and policy, and potentially serve as a model (or warning) for other advanced economies.

One Comment

Comments are closed.