In this week’s podcast, Nathan Paul Southern showed us a far more ominous side to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and its links to organised crime worldwide. Criminal involvement is a little-studied aspect of the BRI, both in policy and research. This is problematic: neglecting to recognise that growth and trade generate huge international risks in situations where governance and regulatory capacities are weak, crime rates are high, and illegal markets are well established increases the danger of systematic criminal exploitation. This article will unpack the true international risks these links hold, as well as delving deeper into how China’s Belt and Road Initiative continues to contribute to the spread and power of transnational organised crime organisations. In this article we will briefly unpack the Belt and Road Initiative before looking closer at the dark intersections.

The BRI

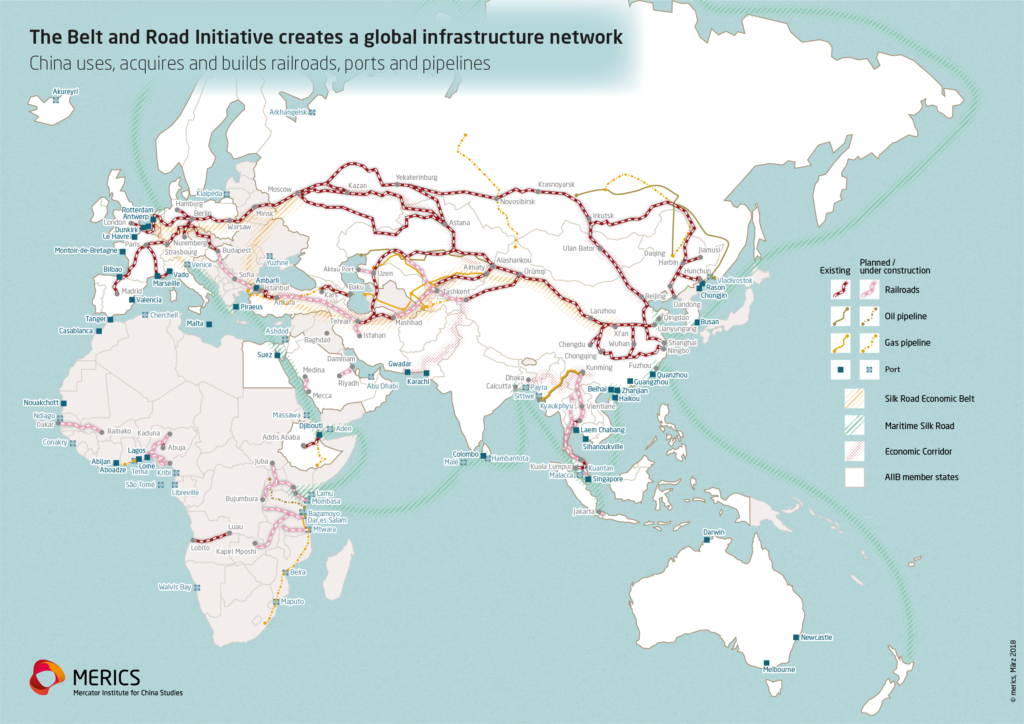

In order to understand the international risks posed by the Belt and Road Initiative, it is firstly crucial to understand what this Chinese led initiative is. Put simply, The People’s Republic of China launched the Belt and Road Initiative with the aim of connecting Asia with Africa and Europe via land and sea networks in order to improve regional integration, increase commerce, and stimulate economic growth. Much of the financing of this international initiative comes from a $1tn infrastructure financing programme. As a result of this programme, China has become the world’s largest donor of development loans, surpassing those of the World Trade Organisation and other Western-led organisations. Unlike loans from other organisations, the Chinese development loans are non-conditional. Loans from the West are often headlined with conditions of how they should be used. Often such prescriptions not only inconvenience developing states, but act as a hindrance to their development entirely. Loans from China on the other hand are given with an ‘all inclusive’ approach, without any pre-set conditions. This makes them far more attractive to states which may not wish to entirely abide by post-Washington consensus economic models.

Further than the theoretical, the global impact of China’s Belt and Road Initiative should not be underestimated. Nowhere is this impact more evident than in the African continent. As China’s economic capacity has grown, so too have ties with the African continent deepened. The World Bank estimates that China is a destination for over 20% of Sub-Saharan exports, and the source of over 12% of its imports. In 2009, China overtook the United States as Africa’s largest trade partner. Many of the development projects taking place in Africa are, at least partially, financed by China and the BRI; having so far invested in 52 out of Africa’s 54 countries, with loans amounting $143 billion since 2000.

In South East Asia, trade has almost doubled since the launch of the BRI. China has poured billions into developing infrastructure, and strengthening its ties with its neighbours. One of the most heavily impacted countries in the region is Cambodia. Since its inception, the BRI has helped Cambodia build and strengthen its infrastructure. Cambodia has been able to connect the capital city to the country’s rural districts, and the newly upgraded infrastructure has boosted both the local and national economies. As we heard in our interview with Nathan Paul Southern, Cambodia plays a particularly important part of discussions surrounding transnational organised crime, and leads us nicely onto exploring the darker side of the Belt and Road Initiative.

The darker side of the BRI

As we have previously mentioned, the loans given out through the BRI seem extremely attractive to developing states, due to the fact that they are non conditional. There have been claims made that China is able to forgo its conditionality as it uses its loans to expand its spheres of influence. As Chinese influence has grown and its economic prowess increased, so too have we seen an expansion in the operations of Chinese organised crime groups. The international risks associated with this criminal expansion are vast. As outlined by Nathan Paul Southern, Chinese organised crime in Asia includes a variety of activities such as online fraud (including pyramid schemes), online gambling, human trafficking (for slavery and prostitution), animal or animal parts trafficking (for use in traditional Chinese medicine), and money laundering (of crime proceeds from the PRC). Nathan discussed how these criminal organisations, through the corridors created by the BRI, have established ‘fraud factories’, massively increasing the online scamming industry, and, in Cambodia, also bringing about questions surrounding human trafficking and slavery. In 2022, the BBC published the story of Yang Weibin who answered a job advert. Soon after, he flew to Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh where he was brought to a nondescript room, had his passport taken away and was forced to work in an online scam centre, also known as a fraud factory. He was among thousands who had been trafficked to work there, and, as we heard from Nathan, the criminal links to the BRI only make such events a larger international risk.

Wider Criminal Risks of the BRI

Apart from the aforementioned expansion of Chinese criminal organisations as a side-effect of the BRI, many scholars fear that the Chinese initiative may also bring with it further opportunities for criminal exploitation. These fears surrounding exploitation predominantly come from the increased proliferation of vulnerable transit routes. Increased connectivity afforded by the BRI may create new chances for organised crime networks at a time when illegal commerce is already spreading drastically over the world and criminal networks are looking for ever more attractive illicit trade routes. When BRI corridors, routes, and commercial hubs are evaluated alongside illicit trafficking routes and hotspots, the overlaps and convergences are obvious. China’s Yunnan province and its capital city, Kunming; Cambodia’s special economic zone and port in Sihanoukville; and Kenya’s maritime and railway hub in Mombasa are among the recurrent locations that serve as both BRI nodes and magnets for trafficking various types of illicit commodities, as well as financial crime and other criminal activities.

To learn more about the belt and road initiative, as well as transnational organised crime in South East Asia, Nathan Paul Southern’s podcast can be found here.